As far back as July 2007 Latino Decisions reported immigration as a top issue for Latinos (see this post here), and immigration remains a top issue according to the tracking poll currently in the field (see October 2010 post here). Previous posts on this website link Latino turnout and vote choice to the issue of immigration. I’m going to dig into this by way of highlighting state-level immigration policy developments and how this influences the way that Latinos view the government and politics in general. I uncover a clear trend in which the presence of an unwelcoming, or anti-immigrant environment leads directly to greater skepticism of government and less political efficacy – a sense that one has a say in what government does. (Stay tuned, in two weeks I’ll look at some fresh data from the 2010 tracking poll)

Last week Thursday, Janet Napolitano, Secretary of Department of Homeland Security (DHS) announced record-breaking immigrant deportation figures for fiscal year 2010. According to DHS (available here), a daily average of 1,080 removals occurred this past year. This figure adds up to the approximately 400,000 individuals that were deported in 2010, more than half who were not listed as convicted criminals.

Many of these deportations come as a result of the Secure Border Initiative, a multi-year plan that increases immigration enforcement on the US-Mexico border. What has been particularly jarring to the Latino community is DHS activity in the interior. Accompanying Napolitano during the statement last week, local sheriffs from Harris County, TX (Houston), LA County, CA, (Los Angeles) and Fairfax County, VA, stood as testimony to the increased coordination between federal immigration enforcement offices and local police departments. Along with 64 other local police department leaders, these sheriffs have signed “Memorandums of Agreement” (MOA) with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), part of a program also known as 287(g) that allows local enforcement officers to assume federal immigration enforcement powers. You can think of 287(g) programs as the teeth to legislative barking like Arizona’s SB1070 and other similar measures. A list of local enforcement agencies participating in 287(g) is available here.

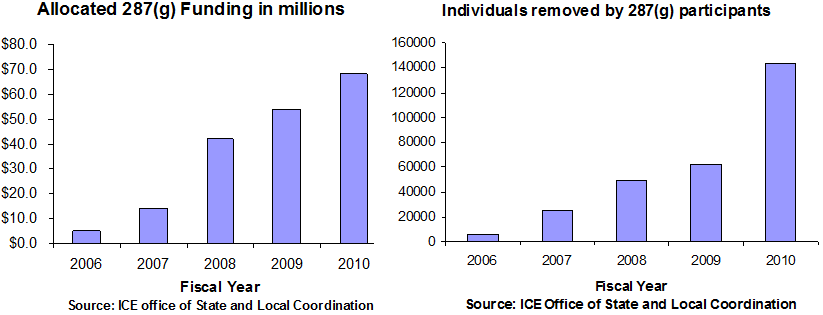

Napolitano credited programs like 287(g) as a major contributor to the new deportation records. Funding for the federal-local coordination program has increased from under $10 million in 2006 to over $40 million in 2008, and now approaches $70 million in 2010. The ICE agency reports a trend in deportations among 287(g) participants that roughly mirrors the pattern in funding. The DHS has addressed the extent to which local immigration enforcement is effectively targeting “criminal aliens” that ICE claims it is most concerned with. What hasn’t been addressed as much is whether this is having an impact on how Latinos view the political system.

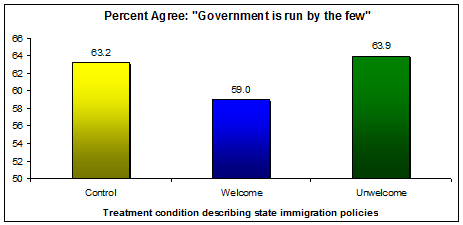

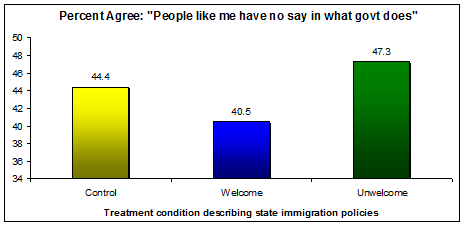

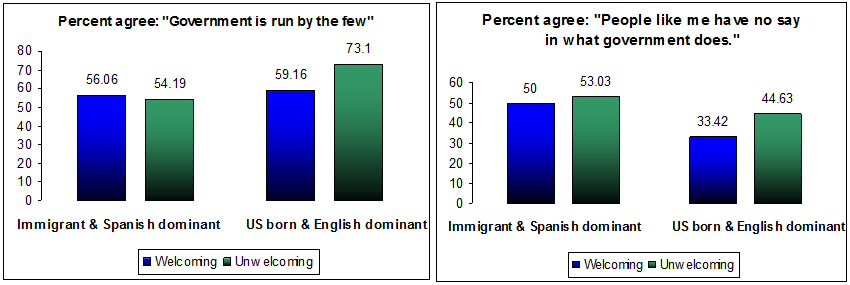

In April 2009 I fielded a survey experiment in the Latino Decisions poll that asked Latino registered voters how much they agreed that “government is run by a few big interests and not for all,” and how much they thought “people like me have no say in what government does.” Just before they answered the question they heard an evaluation of recent state and local immigration policy efforts as either welcoming or unwelcoming towards immigrants.

The results below show how attitudes towards government and a belief that one has a say depend on which “treatment” about state policy toward immigrants that one gets.

For Latinos who get the signal that state immigration policy is unwelcoming, there is a greater incidence of expressing skepticism of government and agreement that “people like me have no say in what government does.”

It would be nice to know whether “treatment” has more or less impact on the 40% of Latino registered voters who are foreign born. After all, state immigration policies like restrictions on driver’s licenses (unwelcoming) or extensions of in-state tuition policies to include undocumented immigrants (welcoming) target the foreign born and not US born citizens. (Click on chart below to enlarge)

Sorting Latino registered voters by nativity and English language reveals that US born Latinos are most sensitive to the difference in treatment. Among the foreign born, Spanish dominant Latinos, whether one gets the signal that state-level policy is welcoming or unwelcoming towards immigrants doesn’t make much difference in views toward the government. However, signaling to US born, English dominant Latinos that state-level policy is anti-immigrant does generate greater levels of skepticism. A similar pattern is revealed with respect to beliefs about whether one has a say in what government does, again, with anti-immigrant environments leading directly to less political efficacy.

A new decade of betrayal?

From 1930 – 1940 the U.S. government forcefully removed hundreds of thousands, (possibly millions?) of Mexican nationals and US citizens of Mexican heritage. Deportations in the 1930s were part of a larger strategy to purge organized workers from agricultural labor markets primarily in California, Texas, Arizona and Colorado. In the aftermath of high-profile immigration workplace raids, like Postville, IA (2008), Mount Pleasant, TX (2008), Chattanooga, TN (2008) and Bellingham, WA (2009), we have learned that US born citizens, many of them children, have been deported along with their parents.

Accompanying the pattern in federal-local coordination for enforcing immigration laws, are the numerous anti-immigrant measures surfacing in city hall meetings. Examples of attempts to ban undocumented immigrants from access to housing have occurred in cities in, among other states, California, Nebraska, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Texas. Measures that restrict employment, property and business owning have also been debated by municipal officials. In large part, resistance to state and local anti-immigrant policies has been led by US born Latinos.

Three things are clear in the analysis of Latinos and the issue of immigration. First, nothing has changed in a direction congruent with Latino immigration policy preferences. Also clear, Latino voters hold Democrats and Republicans responsible for the lack of immigration reform. Finally, it is clear that the impact of anti-immigrant activity at the state and local level, in combination with the local-federal coordination to enforce federal immigration laws, extends beyond undocumented immigrants to Latino citizens, particularly those born in the US. Small wonder, then, why the issue of immigration remains so important to Latinos heading into the November election.

Less clear is whether the first decade of the 21st century will become seared in the minds of Latinos as the new decade of betrayal, and whether this will have long-term impacts on the views that Latinos have towards government.

In the excitement to share the record-breaking deportation numbers, it would seem that Janet Napolitano, along with elected officials on both sides of the aisle, have forgotten that Latinos mobilized in record numbers in 2006. No — not record numbers with respect to Latinos, but rather, record numbers with respect to any peaceful protest or gathering in the history of the United States. Yet, this extraordinary demonstration of support for a specific issue has fallen on deaf ears since 2006. Democrats and Republicans have missed an opportunity to court a growing segment of the electorate. Unfortunately, this missed opportunity may come at the expense of Latinos’ faith in a political system to respond to a key issue, and Latinos’ belief that one has a say in what government does.

Francisco I. Pedraza, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Texas A&M University, and a collaborator on the April 2009 Latino Decisions 100 Days Poll, as well as the current 2010 tracking poll