On November 6, 2012, the residents of Puerto Rico went to the polls to vote on both island-wide general elections and a local plebiscite on the territorial status of Puerto Rico. Almost a month later, during a Whitehouse Press Briefing, a member of the audience asked Jay Carney, President Obama’s Press Secretary, whether the President would assist Puerto Ricans in pursuing statehood. The questioner asserted that: “61 percent of Puerto Ricans voted for statehood” in the 2012 Plebiscite on Puerto Rico Political Status. Press Secretary Jay Carney responded: “Well, I think that the outcome was a little less clear than that, because of the process itself.” The following day local Puerto Rican newspapers published statements attributed to Luis Miranda, the Whitehouse’s Director of Hispanic Media, “correcting” Jay Carney and indicating that President Obama acknowledged that the people of Puerto Rico unequivocally voted in favor of statehood and he was committed to helping Puerto Ricans resolve the island’s enduring status question.

This exchange reflects the complexity of the 2012 plebiscite and the debate surrounding how to interpret the results of the important vote. This blog is a follow up to my earlier discussion of the context of the 2012 plebiscite and addresses the seemingly straightforward question of what was the actual outcome of the vote? I will close this short series of posts on the 2012 Puerto Rican plebiscite with a discussion of the political implications of this vote in the near future.

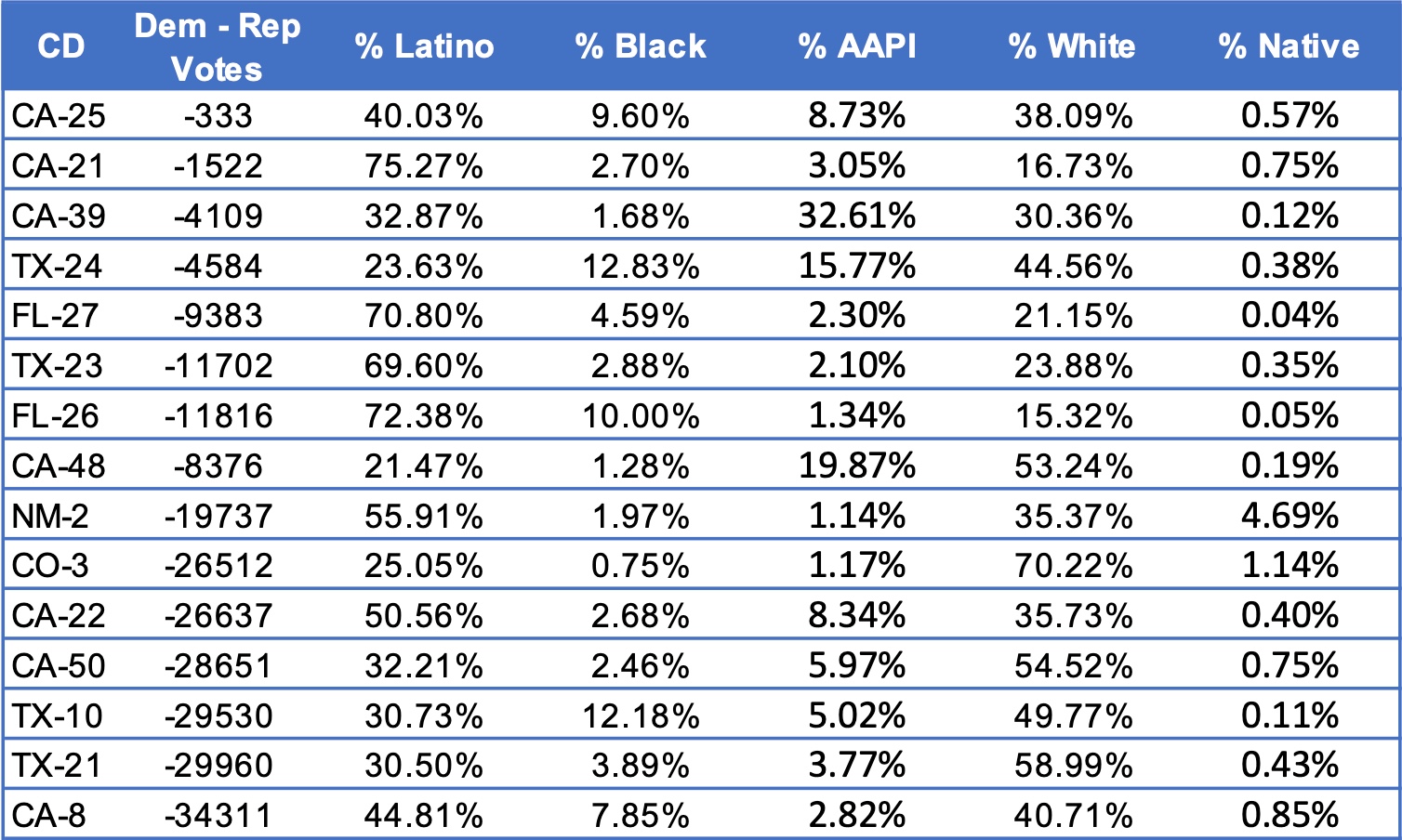

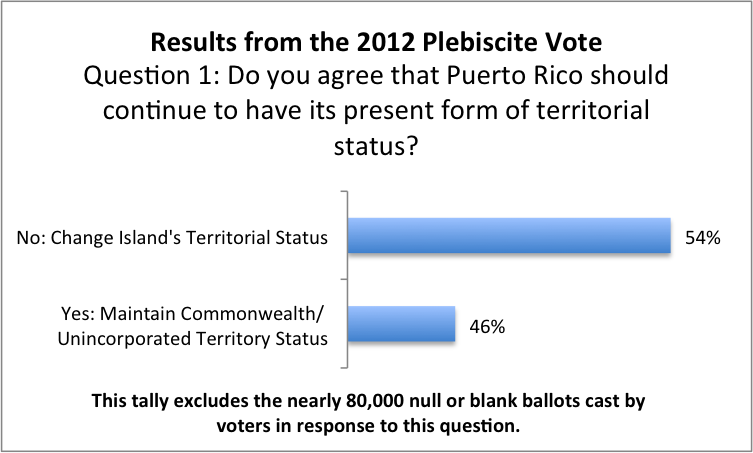

The difficulty associated with interpreting the outcome of the plebiscite vote is due in large part to the process, as reflected in Jay Carney’s quote above. The plebiscite contained two questions. First voters were asked to choose between maintaining the island’s current territorial status (unincorporated territory/Commonwealth) and changing Puerto Rico’s territorial status. A second question required voters to choose among three different specific status options, namely between statehood, independence, or Sovereign Free Associated Statehood (a version of the Enhanced Commonwealth status). As you can see in the figures below, a slim majority of voters supported a change to the island’s territorial status in the first question, with a firm majority of 61% supporting statehood in the second question. Interpretation of the results from the vote is unfortunately not as clean as the figures suggest. The second question eliminated the Commonwealth status as an option for voters, opening up the door for multiple interpretations of the outcome of the vote.

Further complicating matters was the high number of null and blank ballots turned in by voters. While the majority of voters chose one of the three options provided to them, over 480,000 voters did not report a preference to the second question, leaving their ballots blank or writing in a statement of protest. This “blank” option represented 26% of the total number of ballots cast for this question, and has led to many conflicting interpretations of the vote.

(Source: Comisión Estatal de Elecciones, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico)

(Source: Comisión Estatal de Elecciones, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico)

Advocates for statehood have offered three interpretations of the results. First, they argue that a majority of the electorate (54%) voted for a change in the territorial status of Puerto Rico in the first question, and for statehood (61%) in the second question. Second, when raw votes are tabulated, more voters chose the statehood option (824,195) in the second question than for the Commonwealth option (816,978) option from the first question. Finally, several leaders of the PNP argue that “null” or “blank” ballots should not be counted in a democratic vote. In sum, advocates for statehood argue, two-thirds of the electorate voted for statehood in the 2012 plebiscite when “null” ballots are excluded.

Alternatively, critics offer at least four counter interpretations. First, they emphasize the confusing language of the ballot and the fact that the plebiscite was held during the general elections. Second, they contend that the second question eliminated the Commonwealth option presumably prompting 480,916 or 26% of voters to file a blank ballot. Third, they contend that the inclusion of the “Sovereign Free Associated Statehood” option was designed to fragment the territorial autonomy electorate between a Commonwealth and the enhanced sovereignty options. Finally, critics invoke the Sanchez Vilella precedent (see previous post) to include the blank and other protest ballots in the final tally of the results. When including these “protest” ballots, the percentage of voters who chose the statehood option in the second question drops from a robust 61% to 45%, a percentage that is consistent with the pro-statehood outcomes of the 1993 (46.3%) and 1998 (46.5%) plebiscites. This latter argument is premised on the notion that the 2012 plebiscite was authorized by Puerto Rican law and under Puerto Rican electoral law blank and other protest ballots are legitimate forms of democratic expression. It follows that if Puerto Ricans are going to use local laws to demand statehood from Congress, they should also use local standards to explain the outcome of the plebiscite. In sum, critics in Puerto Rico argue that the pro-statehood PNP leadership is actively trying to hoodwink President Obama and Congress by providing misleading interpretations of the 2012 plebiscite.

On December 10, 2012 both houses of the Puerto Rican legislature, presently controlled by a PNP absolute majority, invoked the 10th Amendment and passed concurrent resolutions requesting that President Obama and Congress honor the pro-statehood interpretation of the 2012 plebiscite. Given the complexities associated with the plebiscite voting process, the next question is which interpretation will President Obama and Congress rely upon when making a decision on how to respond? Stay tuned for a follow-up post in this mini-series of blogs focused on the 2012 plebiscite for a discussion of the many implications associated with how Congress and the Obama administration interpret this important vote.

Charles R. Venator-Santiago is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science and the Institute for Latino/a, Caribbean and Latin American Studies at the University of Connecticut

The commentary of this article reflects the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Latino Decisions. Latino Decisions and Pacific Market Research, LLC make no representations about the accuracy of the content of the article.