This summarizes a longer report delivered at the The Rosemary P. and John W. Galbraith Conference on Immigration sponsored by The Miller Center at the University of Virginia. The piece outlines the implications comprehensive immigration reform (CIR) on Latino political behavior based analysis of Latino Decisions research carried out before and after the 2012 election.

The Salience of Immigration Policy to the Latino Electorate

The 2012 election was widely identified as the realization of Latino influence on electoral politics. For the first time in American history, Latino voters were decisive to the presidential election outcome. Had the Latino vote split evenly between Romney and Obama (rather than the overwhelming 75% for President Obama) — Romney would have been elected president.

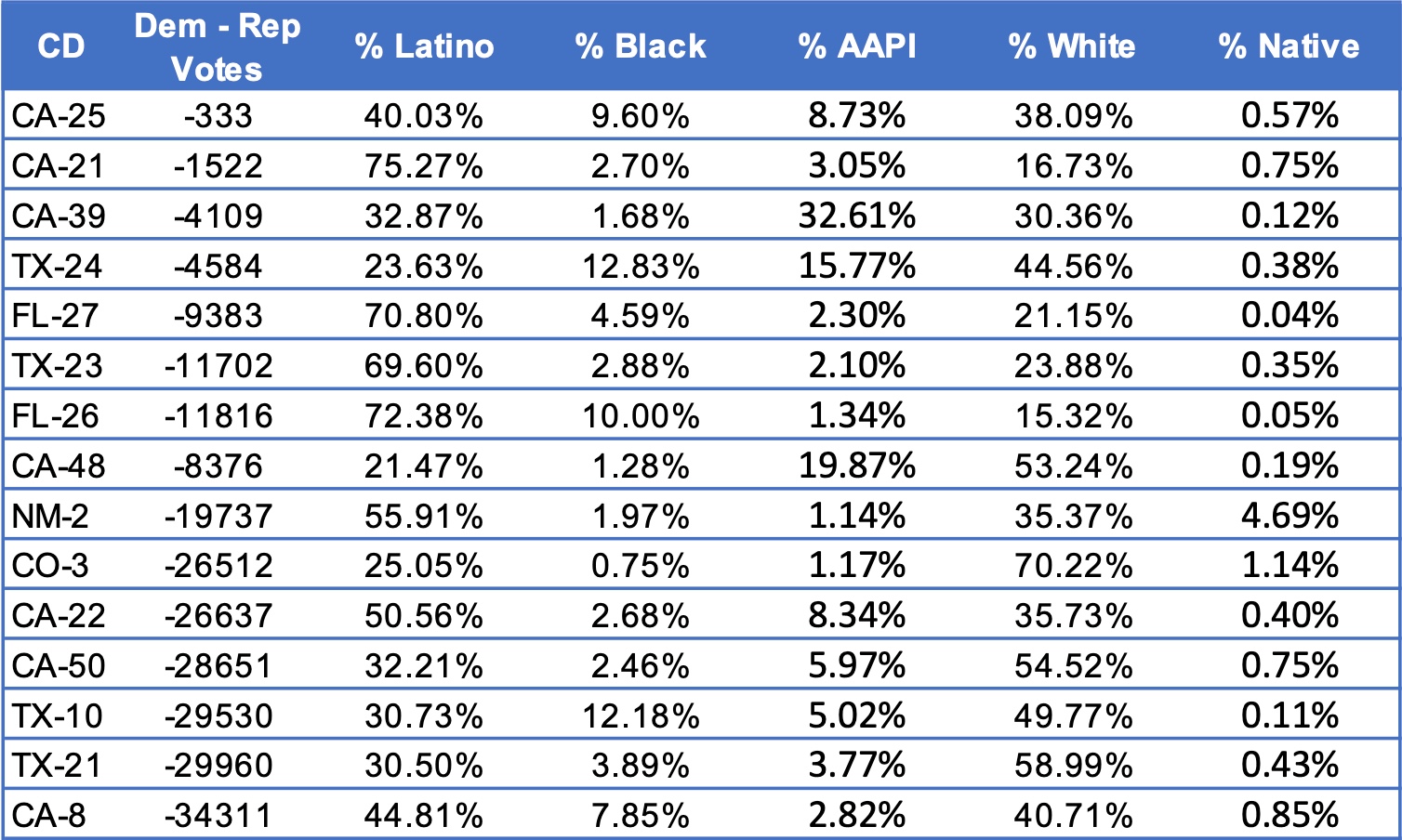

While the economy was the most important issue to Latino voters, immigration remained a point of considerable concern. The impreMedia/Latino Decisions Election Eve Poll found immigration policy ranked second (35%) only to the economy (58%) as the most important issue to the 2012 Latino electorate. This pattern held across states regardless of region (e.g. border states, the west, and new destination states). Interestingly, immigration policy has become even more important to Latino voters since last year’s election. The share indicating immigration is the most important issue the President and Congress should address jumped to 58% in February 2013, and remained steady at 55% by June. We can say with relative certainty that immigration continues to remain a priority to the Latino electorate, and shows no signs of going away any time soon.

The Impact of CIR on Party ID Among Latinos

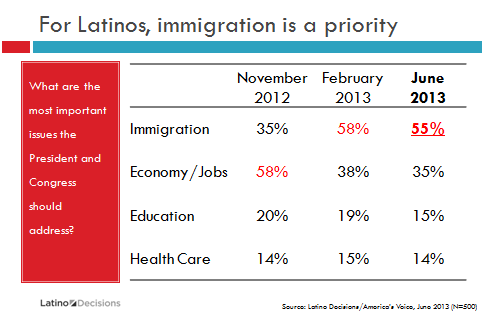

Our studies consistently show immigration reform provides the Republican Party with a unique opportunity to make inroads with Latino voters, who they acknowledge are critical to the party’s survival. For example, a June, 2013 survey shows a third of the Latino electorate (34%) is more likely to support Republican candidates if the party takes a leadership role in advancing comprehensive immigration reform (CIR). There are two important caveats to this point: 1.) a pathway to citizenship must be part of the reform bill, and 2.) the bill must actually pass and become law. It is no secret that a pathway to citizenship is divisive among Republican members of Congress, despite the fact that most Americans support it. Republicans will not be rewarded for blocking CIR or for their verbal attacks on immigrants and Latinos. Back in April, nearly six months ago, when the Senate Gang of Eight first introduced the CIR bill, we found nearly 60% of Latinos said their future support for Republican candidates hinged on immigration reform.

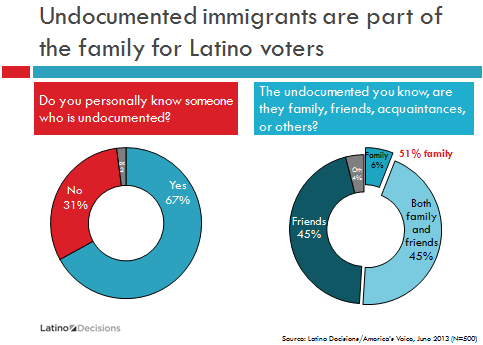

Long Term Consequences of CIR on Electoral Politics

There are significant long-term implications to consider that extend far beyond what happens in the 113th Congress. California offers great perspective on the long-game of immigration politics. A recent post by Matt Barreto and Ricardo Ramirez discusses how Governor Pete Wilson and Prop 187 had the unintended consequence of mobilizing immigrants along with Latino and non-Latino citizens, resulting in higher rates of naturalization, voter turnout, and Democratic party affiliation (Segura, Falcon and Pachon 1997; Barreto and Woods 2005; Barreto, Ramírez, and Woods 2005). Pantoja, Ramírez, and Segura (2001) found California Latino immigrants who naturalized and registered to vote during the Wilson-era were significantly more likely to vote compared to their U.S. born counterparts. Likewise, Barreto, Ramírez and Woods (2005) found the best predictor of California’s Latino turnout in 1996 and 2000 was whether individuals had joined the electorate in the Wilson-era. Harsh political tactics surrounding immigration turned off a large segment of California’s non-Latino voters too, causing the GOP further damage (Segura et al 2006). The overall result is evident today, where Democrats dominate state politics at every level of government.

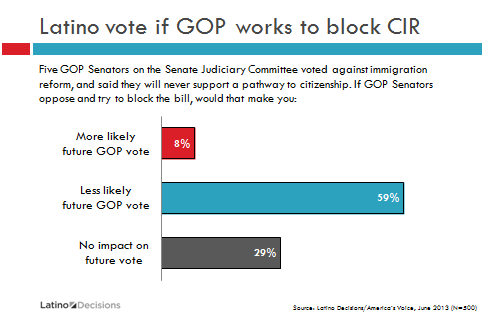

For Latinos, two factors link immigration politics to partisan behavior. First, Latino voters are personally tied to undocumented immigrants. Second, anti-immigration policy positions are consistently accompanied by outward antipathy toward Latinos.

The personal relationship Latino voters have with undocumented immigrants has been well documented by Latino Decisions. A recent poll shows 64% of Latino voters (American citizens by definition) personally know an undocumented immigrant. Most often, these are family members and close friends. Further, 39% of Latino voters report knowing someone who has faced deportation or detention for immigration reasons, an increase of 14 points over 2011, when 25% of Latino voters said the same. In the short time since the “deferred action” program was announced, more than one in five Latino voters (22%) already knew someone who had applied for protections via the deferred action program; another 18% know someone eligible who had not yet. These facts explain why Latinos support CIR so strongly; beyond mere ideology, Latino Americans are personally and directly connected to the people at the heart of the political and policy fight.

There is a strong perception that the immigration debate has created a hostile political climate directed toward Latinos. Back in 2010, 53% of Latino voters said anti-immigrant and anti-Hispanic sentiment across the country was important to their voting decision. By June of 2011, an overwhelming 76% believed an “anti-immigrant or anti-Hispanic environment exists today.” Regardless of immigration status, Latinos realize they too may face discriminatory treatment due to perceptions about their right to be in the United States. In essence, regardless of whether Americans of Latin-origin view themselves as immigrants, others may see them as foreign; this external identification can have significant consequences.

It is highly plausible that the current combination of personal connections to immigrants and hostile political climate could yield a long-term shift in Latino political behavior. Group identity theory research in political science consistently finds perceptions of discrimination motivate ethnic attachments and a sense of common status (Sanchez 2006; Bernal and Martinelli 1993; Masuoka 2006; Uhlaner 1991). For example, Garcia’s (2000) “discriminatory-plus” model suggests shared experiences, including discrimination experiences, lead to collective political efforts. This sense of group identity among Latinos influences both political participation and policy preferences (Sanchez, 2006a; Sanchez, 2006b). If this period of immigration politics produces similar outcomes to those produced in California during the 1990’s, we may look back this point in history as a turning point in Latino politics, and American partisan politics.

Gabriel R. Sanchez is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of New Mexico, Interim Director of the RWJF Center for Health Policy at UNM and Research Director for Latino Decisions.

Work Cited

Alvarez, R. Michael and Lisa Garcia Bedolla. 2003. “The Foundations of Latino Voter Partisanship: Evidence from the 2000 Election,” The Journal of Politics 65: 31-49.

Barreto, Matt A. and Nathan D. Woods. 2005. “ “The Anti-Latino Political Context and its Impact on GOP Detachment and Increasing Latino Voter Turnout in Los Angeles County.” in Gary M. Segura and Shaun Bowler (eds.), Diversity in Democracy, Minority Representation in the United States. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

Barreto, Matt, Ricardo Ramirez, and Nathan Woods. 2005. “Are Naturalized Voters Driving the California Electorate? Measuring the Impact of IRCA Citizens on Latino Voting,” Social Science Quarterly. 86: 792-811.

Garcia, John A. 2000. “The Latino and African American Communities: Bases for Coalition Formation and Political Action” in Immigration and Race: New Challenges for American Democracy, ed. Gerald Jaynes. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Nicholson, Stephen P. and Gary M. Segura. 2005. “Issue Agendas and the Politics of Latino Partisan Identification” in Gary M. Segura and Shaun Bowler (eds.), Diversity in Democracy, Minority Representation in the United States. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

Sanchez, Gabriel 2006a. “The Role of Group Consciousness in Latino Public Opinion,” Political Research Quarterly. 59: 435-446.

Sanchez, Gabriel 2006b. “The Role of Group Consciousness In Political Participation Among Latinos in The United States,” American Politics Research , 34: 427-451.

Segura, Gary M., Dennis Falcon, and Harry Pachon. 1997. “Dynamics of Latino partisanship in California: Immigration, issue salience, and their implications,” Harvard Journal of Hispanic Politics 10: 62-80.

Segura, Gary M., Adrian D. Pantoja, and Ricardo Ramirez. 2001. “Citizens by Choice, Voters by Necessity: Patterns in Political Mobilization by Naturalized Latinos,” Political Research Quarterly. 54 :729-750.

Segura, Gary M., Stephen P. Nicholson, and Shaun Bowler. 2006. “Earthquakes and Aftershocks: Tracking Partisan Identification amid California’s Changing Political Environment.” American Journal of Political Science 50: 146-159.

Uhlaner, Carole 1991. “Perceived Discrimination and Prejudice and the Coalition Prospects of Blacks, Latinos, and Asian Americans .” in Racial and Ethnic Politics in California, Bryan O. Jackson and Michael B. Preston (eds.). Berkeley, CA: IGS Press.

Uhlaner, Carol J. and F. Chris Garcia. 2005. “Learning Which Party Fits, Experience, Ethnic Identity, and the Demographic Foundations of Latino Party Identification” in Gary M. Segura and Shaun Bowler (eds.), Diversity in Democracy, Minority Representation in the United States. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

Wong, Janelle S. 2000. “The Effects of Age and Political Exposure on the Development of Party Identification Among Asian American and Latino Immigrants in the United States,” Political Behavior. 22: 341-371.