Being a son of Mexican immigrants and an El Paso native, born and raised on the eastside, my first thought the morning of the August 3 “active shooter” situation was to call my sister, who lives a short walk from the site of the violence. Her neighborhood and its namesake shopping mall are called “Cielo Vista,” which translates as “sky view” or, now more poignantly, “heaven view.” Later, during lunch at a conference I was attending that weekend, the frequent updates abruptly changed — from mass shooting to massacre.

Days passed before I could fully consider the politics of the assault on people like my family, and those I grew up with in my hometown on the border. We are among those the shooter called a “Hispanic invasion” and the “instigators” he claimed to be responding to. To my advantage, the book I published last year helped me put the attack in perspective — but historical perspective provides both encouragement and a warning: this isn’t over.

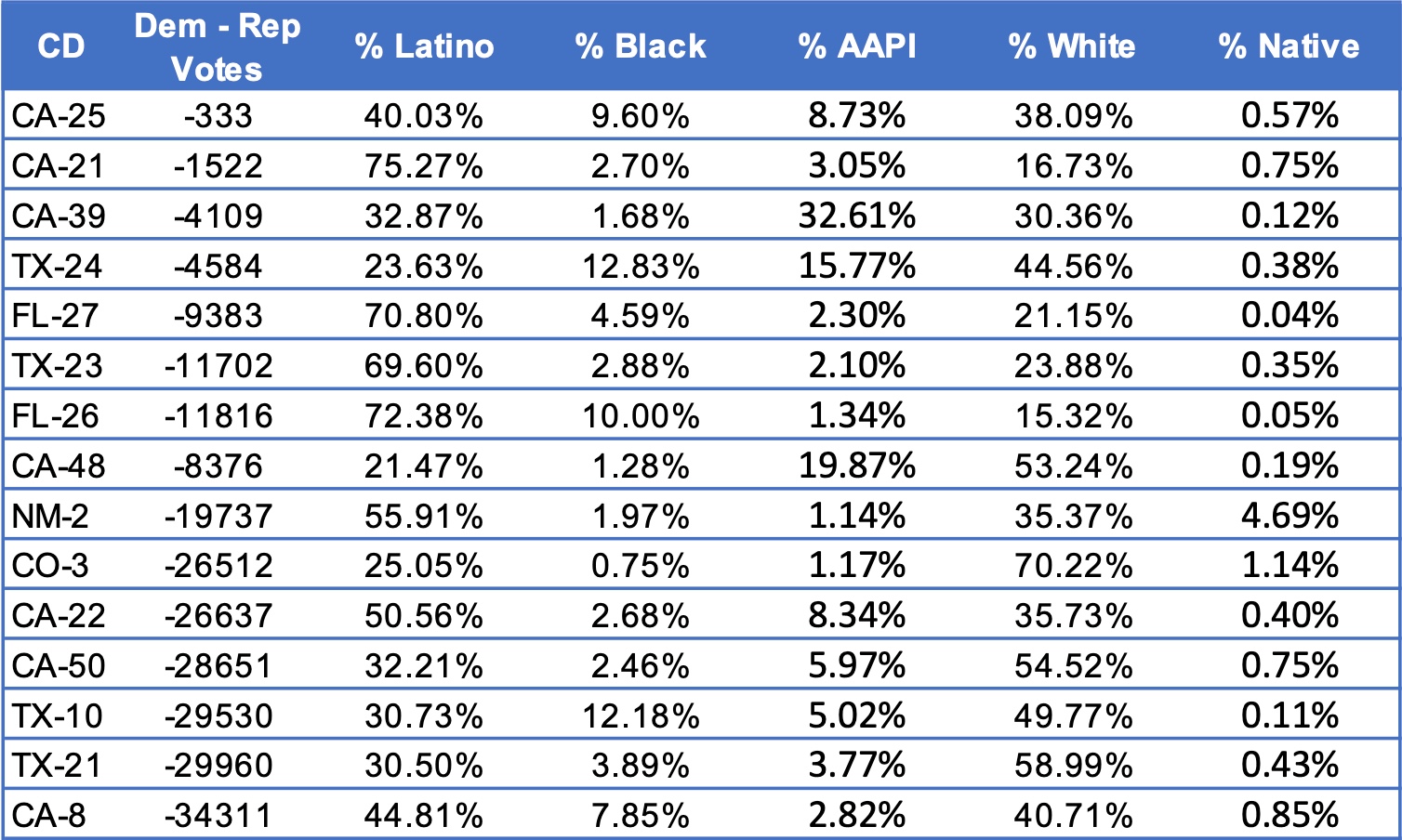

The most remarkable thing about the El Paso shooter’s self-labeled “manifesto” was how clearly it proclaimed the political motive for the attack— to “remove the threat of the Hispanic voting bloc.” Right before the killing began, he posted he wanted to “head the fight” to stop the “invasion” from “taking control of local and state government of my beloved Texas.”

Latino growth and advances have repeatedly “instigated” backlashes, which have sought not only to stop immigration but drive Latinos out of the country. The Hoover administration promoted large-scale repatriation of Mexicans and Mexican Americans in the early 1930s. The Eisenhower administration launched the Operation Wetback mass-deportation campaign in the 1950s. The governor of California staked his reelection in 1994 on a crackdown on undocumented immigrants, codified in ballot initiative Proposition 187 — dubbed “Save Our State.”

In each case, Mexican immigrants conveniently served as defenseless scapegoats during an economic downturn. But the El Paso attack comes during the longest sustained period of economic growth in U.S. history. The current backlash, for the first time, has overtly political causes and goals. The shooter’s manifesto could easily have swapped phrases not only with Donald Trump’s rhetoric but also with an inflammatory fundraising letter the governor of Texas sent out the day before the attack. Decrying and misrepresenting the asylum-seekers at the border as “illegal immigrants,” the governor’s “URGENT” reelection campaign letter portrays immigration as a “disaster” intended to “turn Texas blue” — and it began by proclaiming “If we’re going to DEFEND Texas, we’ll need to take matters into our own hands.”

The history of anti-Latino backlashes and the current one’s particular features suggest we may be only halfway through this wave of enhanced hostility. The de-linking of this campaign of hate from economic conditions, combined with its unprecedented and unrelenting promotion by the president, is particularly troubling. Trump launched the current wave in announcing his bid for the presidency over four years ago, massively refueled it this year, and is expected to continue feeding it through the 2020 elections and beyond.

The positive side of the historical pattern is that, in spite of the recurring backlashes, Latinos have continued to advance politically for a lifetime now. In fact, as has been documented in this post, my book and elsewhere, the last great backlash in 1990s California propelled Latino empowerment efforts forward such that the state’s politics were transformed. Across the country, from Sacramento to the halls of Congress, Latino empowerment has equipped our community with a capacity to resist a backlash like never before — even one personally led by the president. #RememberElPaso