Academics, media pundits, and activists alike have often pointed to the policy and institutional changes that large-scale collective actions can produce. And collective action seems increasingly prevalent, as evidenced by recent mobilizations around Occupy Wall Street, the Trayvon Martin case, and against military intervention in Syria. Yet despite its role in generating social change we still know relatively little about how collective action shapes the political attitudes not only of those engaged in these mobilizations but of those who may be watching from the sidelines. This blog post summarizes findings on this question based on a study of the 2006 wave of immigrant rights demonstrations and their effect on Latino political attitudes towards government that was recently accepted for publication at the American Journal of Political Science.

Spatial and Temporal Proximity to Protests

According to prominent social movement scholars, for members of the general public to support and/or participate in social movements, they must first believe that their actions can make a difference (Goodwin et al. 2004: 421). Thus, the question of whether protests make potential actors feel more efficacious or alienated is of utmost importance.While more optimistic portrayals of social movements have come to dominate the literature on political activism, there is little systematic evidence of the cognitive impacts of protests. Hypothetically, large-scale collective action can have varying (both positive and negative) effects on public attitudes about politics. So do social movements trigger a sense of political efficacy, or instead of political alienation?

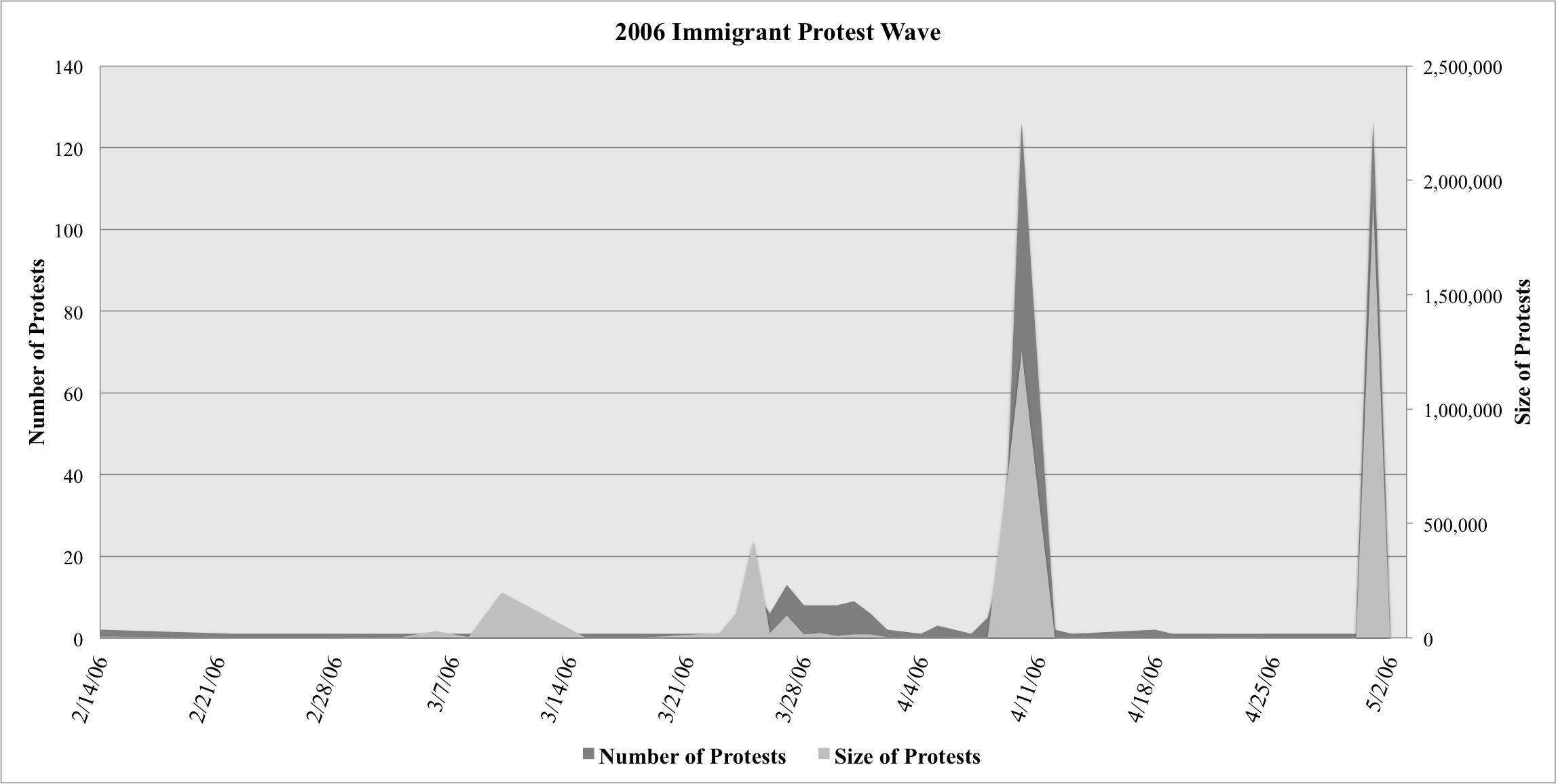

The primarily Latino 2006 protest wave provides an excellent opportunity to explore this research question. In the spring of 2006, up to five million people took part in more than 350 demonstrations across the country in response to proposed federal anti-immigrant legislation, H.R. 4437. In our study, we test how exposure to protests that occurred near where respondents lived shaped their attitudes towards government. To conduct this analysis, we combine the Latino National Survey (LNS) 2006 with our 2006 Immigrant Protest-Event Dataset. The LNS provides a unique vehicle for analyzing the impact of the marches since the survey was in the field before, during, and after the protests occurred.The data allows for the consideration of measures of both spatial and temporal proximity to explain differential results in attitudes towards efficacy, trust in, and alienation from government.

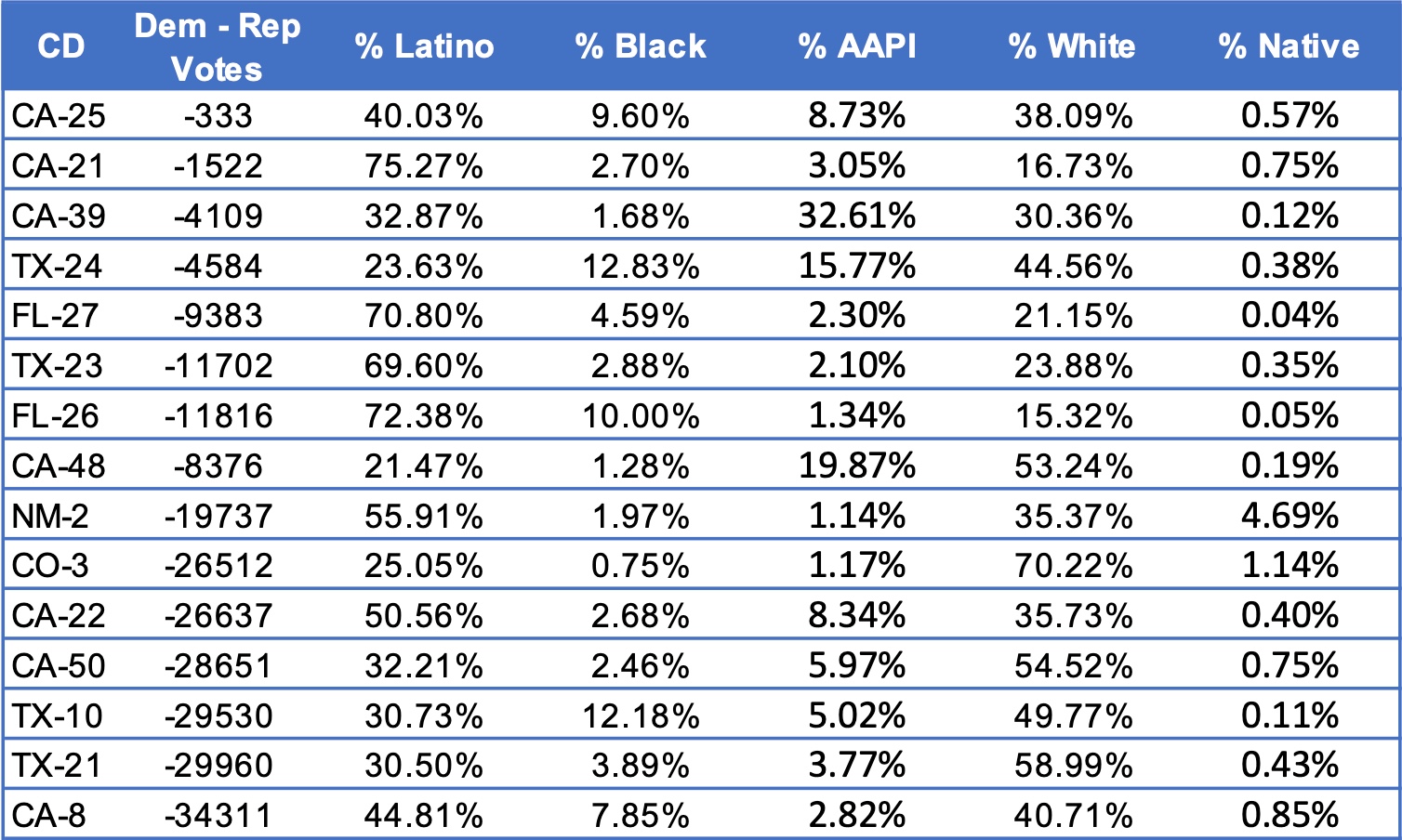

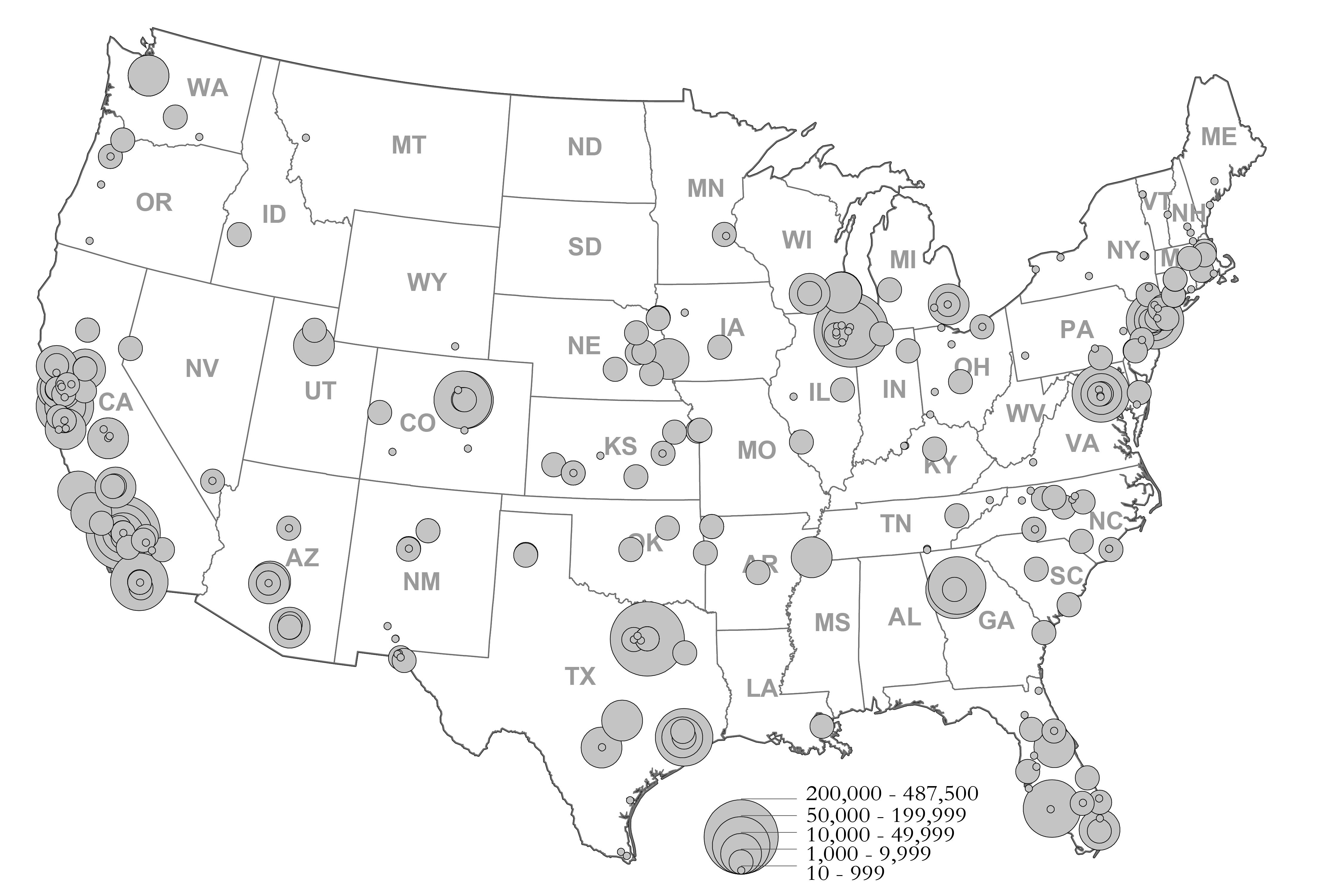

First, we collected and created a protest dataset that contained 357 observations between Feb 14th, 2006- and May 1st 2006. The protests were spread across the country in both traditional immigrant gateways but also new destinations, as indicated by the map below in Figure 1. The distribution of the protests in terms of size and dates is represented in the graph in Figure 2. Second, we identified the addresses of respondents in the LNS to map the distance in time and space for each respondent to each of the protests. Then we created protest measures to capture proximity in terms of time and space for each respondent. In our analysis, we created two protest measures, one that measures exposure to a large protest before the interview, and another that counts the number of small protests that occurred near a respondent before the interview.

Figure 1. Immigrant Rights Marches by Location & Number of Participants during Spring 2006

Figure 2. Number and Size of Protests over the Immigrant Rights Protest- Wave

The focus of our study is on attitudes towards government and our design utilized five different survey items. We include measures of political efficacy, trust in government, and political alienation. This avenue of inquiry is important because scholars have demonstrated that opinions about government have significant effects on political participation and political attitudes. Previous research has shown that Latinos tend to feel less efficacious than other racial and ethnic groups. Additionally, we know little about how political alienation, trust, and efficacy are themselves shaped and formed since we often utilize these measures as explanatory variables, not the outcome for which we want to explain.

In statistical models controlling for education, age, gender, first generation, percent of life in U.S, Spanish dominance, national origin group, and media usage in terms of type and language, our results indicate that proximity to greater numbers of small marches had a positive impact on feelings of political efficacy, whereas exposure to larger protests led to a greater sense of political alienation. The substantive effects reported in the table below indicate that exposure to more small marches reduces the likelihood of agreeing with statements that big interests dominate politics, people have no say in government, and politics is complicated. On the other hand, exposure to large marches had the opposite effect.

Table 1. Substantive Effects of protest variables on Attitudes Towards Government

|

Big Protest |

No. of Small Protests |

|

| Big Interests Dominate |

4%** |

-9%* |

| No Say in Government |

3%** |

-8%* |

| Politics is Complicated |

3%** |

-7%+ |

| ** p<0.01, * p<0.05, + p<0.1 |

In contextualizing our results with interview data with immigrant rights activists across the country, we argue that the differing effects protests have on attitudes hinge on the types of frames deployed at large versus small marches. Large marches often contained both the mainstream “We are America” frame and a more radical frame that was critical of the U.S. government. We argue the latter frame was more likely to be covered negatively by the media and, consequently, resulted in Latinos having less confidence in our political system. Conversely, small marches often contained a more unified mainstream “pro-American” frame that emphasized immigrant integration and their potential to influence the political process.

Conclusion and Implications

Early explanations of social movements portrayed collective political activism as irrational acts by disgruntled individuals that could easily spread to alienated segments of society and threaten democracy. Since then, social movement scholars have established that large-scale collective action is often motivated by political beliefs and a commitment to social justice. As noted by the achievements of the civil rights, women’s suffrage, environmental, and other American social movements, mass activism can contribute to producing important policy changes. With regard to the historic 2006 immigrant rights marches in particular, no such legislative change was accomplished. Yet just because some form of legalization was not passed in 2006 does not mean that the national protest wave had no effects. As indicated by the findings briefly presented in this report, the mass marches contributed to producing important changes in Latino public opinion. Our results indicate that large-scale immigrant rights activism shifted how Latinos view the U.S. political system and their own abilities to influence the outcomes of government. Activists and policymakers should take note of these findings as they devise their strategies for their current campaign to pass comprehensive immigration reform.

Michael Jones-Correa is a Professor of Government at Cornell University, Sophia J. Wallace is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Rutgers University, and Chris Zepeda-Millán is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Loyola Marymount University.

Full Citation for the Study:

Wallace, Sophia J., Chris Zepeda- Millán and Michael Jones-Correa. Forthcoming. Spatial and Temporal Proximity: Examining the Effects of Protests on Political Attitudes. American Journal of Political Science. Published Online Sept. 2013.

References Cited

Goodwin, Jeff, James Jasper, and Francesca Polletta.2004. “Emotional Dimensions of Social Movements.” In The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, eds. David Snow, Sarah Soule, and Hanspeter Kriesi. Malden: Blackwell Press, 413-432.

The commentary of this article reflects the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Latino Decisions. Latino Decisions and Pacific Market Research, LLC make no representations about the accuracy of the content of the article.