By Gabriel R. Sanchez, Stephen A. Nuño, and Matt A. Barreto

Following the Crawford v. Marion County Election Board decision of the Supreme Court which upheld the stringent photo-identification policy for voters in Indiana, several other states have or are considering similar reforms to their election laws. Most recently, Governor Nikki Haley of South Carolina signed the state’s photo-ID bill into law, making South Carolina the tenth state to adopt this type of voter identification legislation. According to the National Conference of State Legislators, a total of 33 states have considered adding or strengthening voter identification requirements this year, and 28 states already have broader requirements than what HAVA mandates. Among these states, the Texas House just passed legislation requiring voters to show photo identification before being able to vote, sending the bill to Governor Rick Perry who is likely to sign this legislation into law shortly. Similar legislation was unsuccessful in New Mexico’s legislative session, but given that this is a high priority of the new Republican Governor (Susana Martinez), it is likely that this will not be the final vote on this issue in the majority-Latino state.

In this post we draw from some of our recent academic research to address one specific point: Does access to required forms of identification vary by racial/ethnic group in the population. In 2007 we presented a paper at the American Political Science Association conference finding minorities would be disadvantaged by strict identification laws. In 2009 we published a research paper in PS: Political Science & Politics which found that under Indiana’s photo-ID law, African Americans were significantly less likely to have the proper credentials to register or vote. Here, we re-examine this question with a new national dataset of registered voters following the 2008 election, and find that minority and foreign-born voters are less likely to have a valid photo-ID. Therefore, these laws place a disproportionate and additional cost to voting for specific segments of the electorate.

Does Access to Required Forms of Identification Vary Across the Population?

We contend that while instilling greater confidence in our election system (the primary benefit of Photo-ID laws) is a worthwhile goal, it is equally important to examine the impact that more rigorous identification requirements may have on the law abiding electorate. In our research we hypothesize that adding photo-identification requirements would create a substantive barrier to voting for racial and ethnic minorities, as well as foreign-born voters. We base our theory on the clearly established relationship that institutional burdens to participation have on individuals who have fewer political resources.

Attempts to analyze the impact of restrictive laws on voter registration and turnout have consistently concluded that turnout rates are higher when costs associated with voting are low (see: Campbell et al. 1960; Wolfinger and Rosenstone 1980; Katosh andTraugott 1982; Jackson 1993; Blank 1974; Kim, Petrocik, and Enokson 1975; Bauer 1990). However, very little is known about the direct effects of voter identification laws.

To examine the impact of these specific institutional changes to the voting system we rely on the Collaborative Multi-Racial Political Study (2008), a national telephone survey (n= 4,563) of registered voters who were likely to vote in the 2008 presidential election. In this survey, we asked registered voters if they currently had a valid driver’s license or state issued photo-ID. Respondents were then asked if this ID was expired, if the name on that ID matched that on their voter registration record, and if the address on both the registration record and the ID matched. Thus, we are able to provide a strong assessment of how many currently registered voters within the electorate lack photo-identification.[1] Furthermore, with over-samples of African Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinos, this data-set provides a key instrument to test whether access to photo-identification varies across race, ethnicity, and nativity.

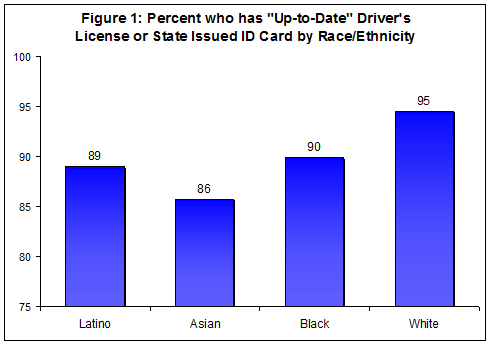

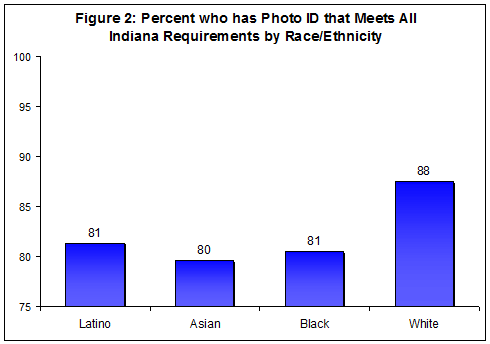

As depicted in Figure 1 above, the vast majority of likely voters do indicate that they have a valid driver’s license or state issued identification card when queried. However, there is a meaningful difference in access by race, with a 9% gap between Asian American and White registered voters, a 6% gap between Latinos and Whites, and 5% gap between African American and White registered voters. Furthermore, when we dig deeper in our inquiry and explore the frequency of valid identification across more stringent requirement levels, greater disparities across racial and ethnic groups emerge. For example, when we identify respondents who meet all three requirements (see criterion in above paragraph) that could now be required in states following the Indiana decision, we see a significant decrease in registered voters who have “valid” identification. As depicted in Figure 2, we see a similar racial and ethnic gap, with White respondents clearly having the highest rates of valid identification (88%), followed by Blacks and Latinos (both 81%), and Asian American (80%) registered voters. Therefore, across all groups, it is clear that access to “valid” identification decreases significantly as we move to more stringent qualifications, yet Latinos, African Americans and Asian Americans are less likely to have a state issued ID that meets the criterion established by the Supreme Court. The gap between white and African American likely voters is very similar to what we have found previously in Indiana, and the gap between Latino and white voters similar to those found in three western states (CA, NM, WN).

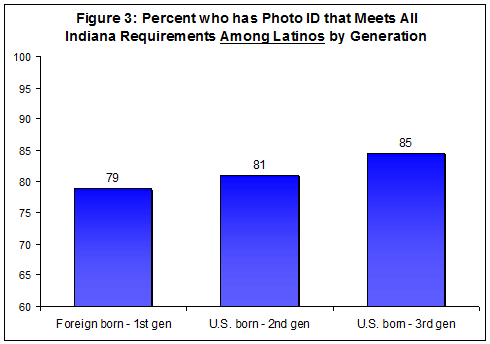

Finally, in Figure 3 below we compare access to photo-identification that meets all three requirements by nativity among Latinos in our sample. Again, we see a gap in Latino voters who have a photo-identification with a name and address that matches their voter registration information between those who are foreign born (79%) and those who are 2nd generation U.S. born (81%) and 3rd generation U.S. born (85%). These trends are highly consistent with those we have identified in some of our earlier work focused on the states of California, New Mexico, and Washington, and support our theory that requiring photo-IDs would disproportionately impact voters with fewer resources. In our previous work, we found that foreign-born voters were less likely than US-born voters to have a driver’s license, even when we controlled for a host of other factors.

While the courts and now the Federal government have cleared certain photo-ID laws, the costs appear to be greater than the perceived benefits. While we strongly support laws that improve the integrity of our election system, voter-ID laws are creating barriers to participation that are having disproportionate impacts on lower-resource citizens. Indeed, as research by Prof. Lori Minnite has shown, the occurrence of voter fraud whereby people ineligible to vote, fake their way into voting is extremely rare. Instead, we argue that more attention should be given to those areas where election fraud is more likely to exist, such as the point of contact between the ballot and officials counting the vote, absentee voting and registration fraud.

Gabriel R. Sanchez is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of New Mexico and Research Director for Latino Decisions. Stephen A. Nuño is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Northern Arizona University and a past contributor to the Latino Decisions blog. Matt A. Barreto is a co-founder of Latino Decisions and an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Washington. These three authors have collaborated on researching the effects of voter ID laws for the past five years.

[1] Our research design focuses on registered and likely voters. An ideal population for this analysis, as those found here to lack valid identification are likely to attempt to vote in upcoming elections, and thus will be impacted by more stringent voting requirements. This however ensures that our data will provide a conservative estimate of citizens who lack valid identification, as likely voters typically have greater resources than non-voters.

Works Cited in Post

Bauer, John R. 1990. “Patterns of Voter Turnout in the American States.” Social Science Quarterly 71: 824–34.

Blank, Robert H. 1974. “Socio-Economic Determinism of Voting Turnout: A Challenge.” Journal of Politics 36: 731–52.

Campbell, Angus, Philip E. Converse,Warren E. Miller, and Donald E.Stokes. 1960. The American Voter. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jackson, Robert A. 1993. “Voter Mobilization in the 1986 Midterm Election.” Journal of Politics 55: 1081–99.

Katosh, John P., and Michael W. Traugott. 1982. “Costs and Values in the Calculus ofVoting.” American Journal of Political Science 26: 361.

Kim, Jae-On, John R. Petrocik, and Stephen N. Enokson. 1975. “Voter Turnout among the American States: Systemic and Individual Components.”American Political Science Review 69: 107–31.

Wolfinger, Raymond E., and Steven J. Rosenstone. 1980. Who Votes? New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.