Findings in The Pew Hispanic Center’s recent study, “When Labels Don’t Fit: Hispanics and Their Views of Identity” generated buzz among those interested in the dynamics of ethnic identity and American politics. The report highlighted the fact that most Latinos do not use the panethnic terms “Latino or Hispanic” to describe themselves, instead preferring more specific references to their family’s heritage or national origin (e.g. Puerto Rican, Cuban, Mexican, Colombian, etc.).

This finding has been substantiated over the last three decades by academic research in varied disciplines that consistently finds the same preference for national origin identifiers over panethnic terms. Ironically, even when reporting the limited incorporation of pan-ethnic identity, the terms – “Latinos” or “Hispanics”– are to describe the populations and results.

The identity preference trend, and public interest in it, illustrate the enduring and evolving discussion about the relevance and presence of a Latino pan ethnic identity and its impact on the daily life for many Latinos. The Pew identity study is an impetus for a timely dialogue regarding the nature, scope, and development of pan ethnic Latino/Hispanic identity in the United States.

Capturing Latino Identity As It Evolves

One can hardly go a day without running into a reference to Hispanics or Latinos; but meaning, formation and attachments to those terms are less frequently encountered. The social and political forces driving how people of Latino origin see and define themselves (individually and to other identity groups) have evolved over the last fifty years. For example, in the 1960’s, the discussion focused primarily on the labels “Mexican American” and “Chicano”, differences between the terms, and the authenticity of each. Most are familiar with the demographic changes within the Latino population especially since the mid – 1980’s: more national origin groups, more immigrants, more that have been in the United States for more than one generation, more geographic dispersion. The composition and distribution of the Latino population in the United States is much different than it was ten, twenty or thirty years ago.

For the most part, regional concentration kept many of the Latino origin groups relatively separated (e.g. Puerto Ricans in New York, Mexicans in the Southwest and Cubans in Miami). There were few contexts where these groups might interact – in person or shared media consumption. The result of substantial Latino migration, both into and within the United States, has lessened geographic divisions. Spanish and English media, political and commercial, targeting the diverse group of people with Latin American and the Iberian Peninsula origins (with continued population dominance of the Mexican origin community) facilitates social linkages across groups that were not as prevalent in prior generations as well.

These developments leave us puzzled, trying to figure out who these communities are, and whether it is appropriate to consider them a unique kind of group aggregation. Research on earlier waves of European migration noted that Italian immigrants thought of themselves within the context of sub-regions and local communities within Italy. Their experiences in the U.S. resulted into the “creation” of Italian Americans.

Studies have examined the fluid and contextual nature of Latino identity. That is to say, in different settings one may have a heightened sense of national origin, while in another context pan-ethnicity has more meaning. Others have evaluated the relationship between political engagement and identity choices. Yet another line of inquiry explores the bases individuals acquire these identities. Accurate interpretation of these findings however, requires examining the survey and methodology: how were identity questions asked, how many different questions about identity were there, what were the response options, how many responses were allowed, were they rank ordered, what is the demographic profile of the survey respondents? These differences can produce very different results and color our interpretation of the findings.

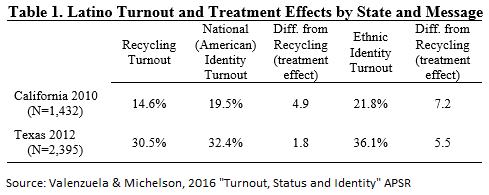

Over time, and many studies across many disciplines, there are major points of accord that inform our understanding of unique Latino/Hispanic identity: 1) Latino identity is a social construct as opposed to an innately derived “trait”. 2) It is a process whereby individuals through a myriad of experiences, socialization, and their own cognitive development connect to societal categorization of different groupings. 3) Whether ethnic/national origin or pan ethnic identity is present, there is a greater likelihood Latino-origin individuals subscribe to multiple identification terms. 4) Presence or use of a pan-ethnicity is likely driven by the situational context and racial/ethnic milieu an individual finds herself in. 5) While, it is the individual that formulates an identity, the impact of social structures, public policies, and historical vestiges play a major role in this formulation process. 6) Social networks, cultural values and practices, and nativity status contribute to the formulation of a pan-ethnic identity or not. 7) There are emotive and affinity related connections with identity that affects one’s self –concept and group associations. 8 ) With the presence of a national origin and/or pan ethnic identity, there can be variation as to choices of preferred and used labels.

Complexity, Common Knowledge, and Advancing Understanding

Journalistic narratives and countless academic publications have discussed and re-conceptualized how and why social identity manifests for persons of Latino ancestry in the United States. A common theme among those researching and writing about Latinos is harping on the complexities of this social phenomenon. There are many: what term(s) a person may use to call themselves, how one Latino identity group relates to another, how cognitive understanding of oneself develop, what feelings of self are associated with the different identities?, and so many more.

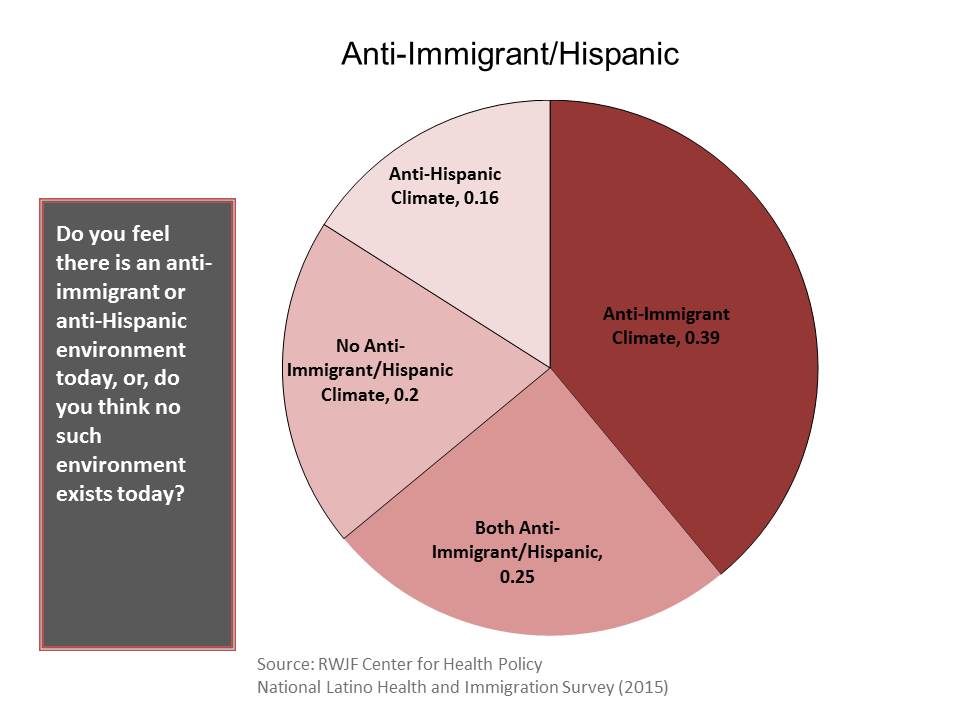

At the same time, many people would respond that ethnic and other kinds of identity are a matter of common knowledge; people of all kinds identify with different social groups and frequently use labels of association in our everyday lives. Latinos/Hispanics live everywhere in the United States and an entire continent south of us (with presence on a couple more). They are evident in mass media, advertising, and polls. Many Latinos in the United States find themselves targeted by punitive policies, the subject of negative public perception, and at the lower rungs of the socio-economic ladder.

Latinos have communities of interaction across social networks, familial ties, and households. These communities are influenced by societal attitudes (among Latinos and non-Latinos alike) and policies that have created and perpetuated an ongoing awareness and understanding of being Latino/Hispanic in the U.S. Thus, a Latino experience is formed from within (the groups) and imposed from outside the group too.

The continued exploration and discussions about Latino/Hispanic identity should incorporate the complexities and relate these social identities to pragmatic situations. One way to advance our understanding is sharing information and data for multiple minds and eyes to analyze, provide different perspectives and approaches, and partake in the exchange of ideas and evidence to further our knowledge and its application. Collectively, by incorporating complexities and everyday general notions about ourselves and world we live in, we are presented with a continuous set of challenges and opportunities to extend our conversations critically, analytically and more focused to move toward a more thorough understanding of social identity

It is clear that no one study will definitively answer or resolve the existence, relevance, acceptance, and utility of a pan-ethnic identity. I would encourage more of my colleagues to commit to data sharing as research shows, the more often this occurs, the greater the proliferation of knowledge and understanding. In the case of the Pew Hispanic Center, they initiated a policy several years ago to make their data publicly available to interested parties. Many researchers deposit their studies in well-maintained research archives. Such practices have enabled journalists, researchers, policy makers, and advocates to view and examine these studies from different perspectives and seek answers to a wide range of questions about Latino identity and its sociopolitical implications.

The Latino/Hispanic communities are active, dynamic, knowledgeable, engaged, frustrated, road weary, optimistic, pragmatic, trying to survive, and even thrive. Group affiliations and connections will continue to be relevant and subject to the dynamic forces that shape and give it meaning. Let’s keep on exploring identity and compare the findings by integrating complexities; insuring clarity in what we are asking and how we follow through on our search for relationships and answers, while maintaining an eye toward applying that knowledge to affect these communities.

John Garcia is director of the Resource Center for Minority Data and ICPSR’s Director of Community Outreach. His academic career focused on Latino politics spans over thirty years and scores of publications. He holds the distinction of contributing to the three largest academic surveys on Latino social and political life in the United States – The National Chicano Survey (1980), The National Latino Political Survey (1989, co-PI), and The National Latino Survey (2006, co-PI).

The commentary of this article reflect the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Latino Decisions. Latino Decisions and Pacific Market Research, LLC make no representations about the accuracy of the content of the article.