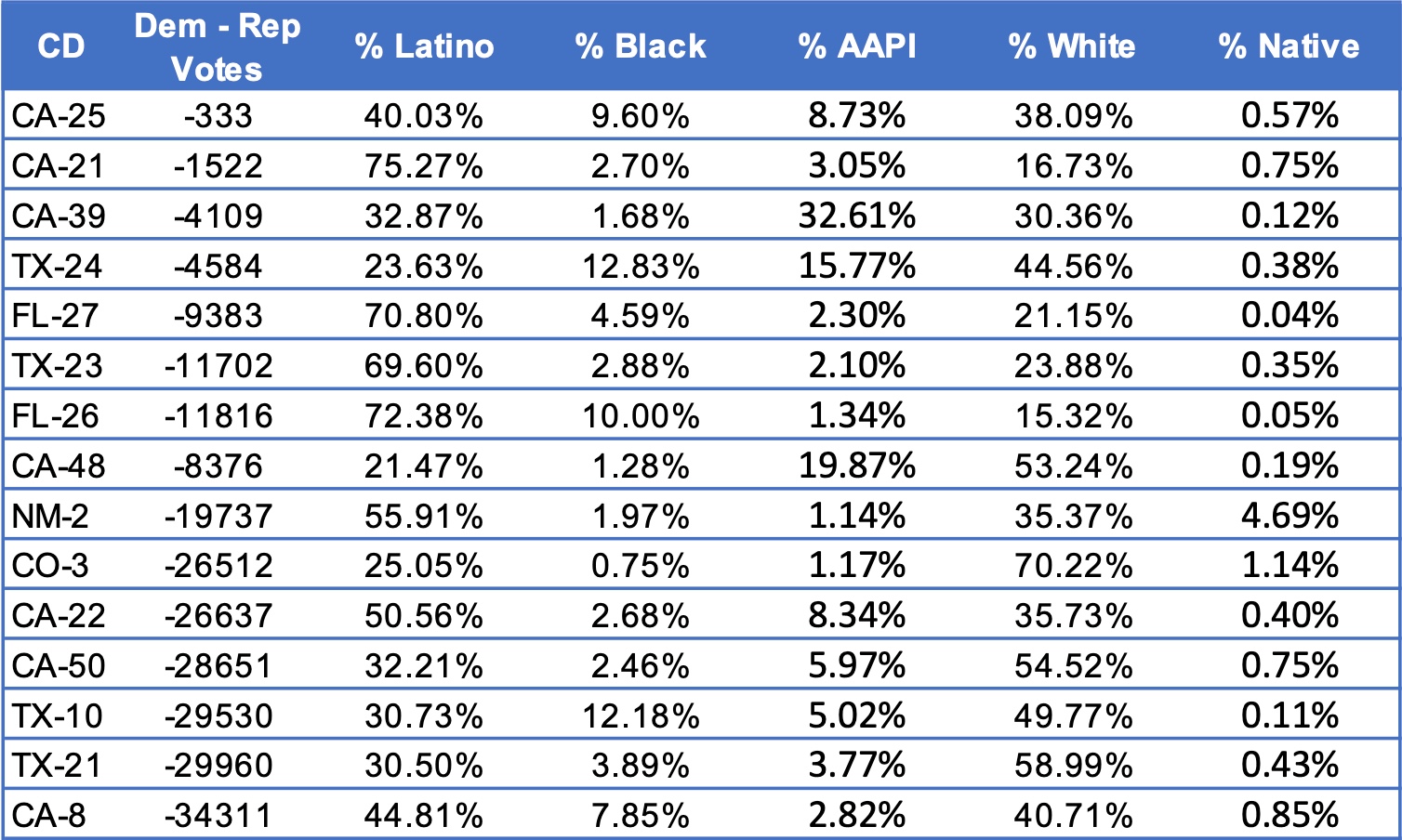

The United States government has been deporting large numbers of undocumented migrants as of late (see Figure 1 below), and the majority of them are Latino. In addition to negatively affecting the individuals removed from the country, this policy also affects many people who remain, such as US-citizen family members. Drawing on a study of U.S.-born Latinos who are the children of immigrants, Michael Jones-Correa, Alex Street and Chris Zepeda-Millán find that when young Latino citizens become aware of the Obama administration’s deportation policies, they view the Democratic Party as significantly less welcoming. Given that partisan attachments formed by young adulthood tend to persist through voters’ lives, this suggests that current deportation policies have the potential to alienate Latino voters from the Democratic Party for decades.

In the first five years of the Obama administration, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) issued removal orders to nearly two million people, at a rate 1.5 times higher than the average under President G. W. Bush.* Many of those deported in recent years have strong ties to people still living in the U.S., such as their U.S.-citizen children. The ongoing policy of mass deportations is reconfiguring a significant portion of American society, both by excluding people who were once residents and by re-shaping the families and communities that remain.

There are about 33 million U.S.-born children of immigrants living in the United States today. Around 9 million of them live in mixed status households, along with one or more undocumented migrants. Most, though not all, of these young Americans are Latino. We surveyed a national sample of 1,050 young (18-31 year old) US-born Latinos whose parents were born in Latin America. This group is ideally suited for studying the long-term implications of mass deportation policies on the future of Latino, and, ultimately, American politics.

Consistent with Latino Decisions findings on this topic, many of the U.S.-born Latinos in our sample have close ties to undocumented residents or people who have been deported: 21% report that a close (5%) or more distant (16%) family member has been deported. This figure rises to 27% when we include friends. In addition, 46% have at least one parent who lived for a period as an undocumented migrant in the U.S. In addition to the close connection, survey participants were heavily in favor of regularization for undocumented migrants and 72% agreed with the statement, “Do you think how undocumented immigrants are viewed by the general public also affects how U.S.-born Latinos are viewed?” The latter finding suggests that U.S.-born Latinos may perceive policies targeting the undocumented as attacks on themselves as well.

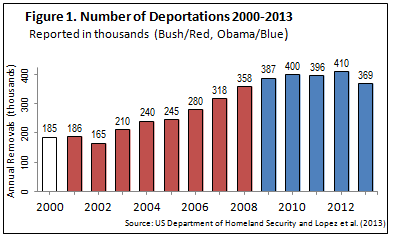

Somewhat surprisingly, as reflected in the figure below, we found that overall knowledge of the Obama administration’s deportation policies is limited. Survey participants were asked: “Do you know roughly how many undocumented migrants the Obama administration has deported each year? If you’re not sure, please give us your best guess. Is it less than under President Bush, about the same as President Bush, or more than President Bush?” 39% of those taking part in the survey opted for “Don’t know,” another 26% said “more,” 19% said “the same” and 16% said “less.” The correct response is “more” which indicates that only a quarter of the sample was accurate in their perceptions.

There is some indication in Figure 2 that people personally acquainted with deportees are better informed, though the difference is not statistically significant. Those with parents with experience as undocumented migrants are more knowledgeable, as are those who are either “somewhat” or “very” interested in politics. Spanish media use is not significantly associated with greater knowledge in our sample.

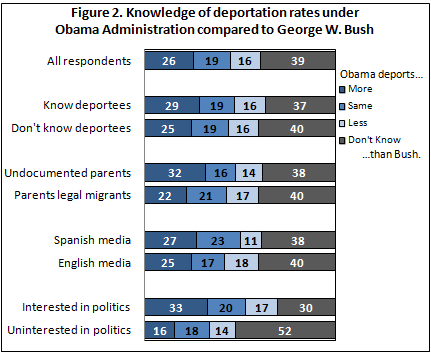

Our study then tested the effect of additional knowledge of mass deportations by randomly assigning half of the survey participants, after answering the question on deportations under the last two presidents, with the following: “In fact, the Obama administration has deported around one and half times more people each year than the average under President Bush.” We then asked survey participants whether they see the Democratic and Republican parties as “welcoming, unwelcoming, or neither welcoming nor unwelcoming toward Latinos.” In the control condition with no additional information 55% of respondents rated the Democrats as “welcoming,” compared to 45% among those who received the additional information on deportations; this difference is statistically significant. Learning that Obama has been deporting more people per year than his predecessor makes Latinos view the Democratic Party as less welcoming. Only 9% of our sample rated the Republican Party as welcoming to Latinos, with no significant effects for the experiment.

The effects of additional information on deportations under President Obama are larger for those who are the least informed. In the figure below, significant effects are observed among those who admitted they didn’t know, and among those who gave the most inaccurate answer-Obama deports less than Bush. The dots in the figure show the difference in the percentage rating the Democrats as “welcoming,” comparing the answers of those told that Obama has been deporting more people than Bush, to the responses of those who did not receive this additional information. The figure below shows that when compared to those who said “don’t know” to the question about deportations under Obama vs. Bush with no follow up, people told the correct answer were around 24% less likely to say that the Democrats are welcoming toward Latinos. The horizontal lines through each point show 95% confidence intervals.

We observe significant, negative effects on evaluations of the Democratic Party as “welcoming” to Latinos, both among people who had earlier described themselves as Democrats, and among those who self-identified as Republicans. Consistent with other research, we found no effect for “strong” Democrats. Committed partisans tend to resist information that is not consistent with their political views. But the population of young, US-born Latinos includes many weak partisans and political independents, leaving plenty of scope for information about deportations to have an effect.

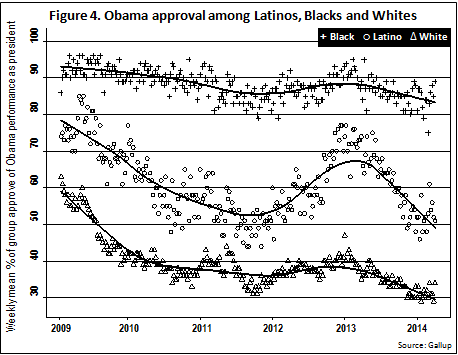

Despite support for Obama among Latinos in 2008 and 2012, affiliation with the Democratic Party remains unstable. Broader fluctuations in Latino party evaluations are illustrated in Figure 4, showing approval ratings for Obama. Latinos–particularly newer voters–are not yet firm Democrats.

Although Latinos tend to identify with the Democratic Party, many young potential Latino voters actually have poor information about the Obama administration’s immigration policies. When informed of these policies—as both Latino civil rights groups and mainstream Spanish-language news outlets have increasingly done since our experiment was conducted—their views of the Democratic Party become markedly more negative. Prior research shows that the attachments that young people from to political parties can last for many years. If young Latinos respond to information about the Obama administration’s deportation policies by distancing themselves from the Democratic Party, the effects may persist for decades.

_________________________

* Immigration law does not provide a single, historically stable category of deportations. So-called “returns” of migrants apprehended at the US border peaked at 2 million a year under President Clinton in the year 2000. Since then, the number of returns has fallen but ICE has sharply increased the number of “removal” orders, which criminalize re-entry. Under both G. W. Bush and Obama, this increase has been cited as evidence of more robust immigration enforcement, and the Obama administration has publicized the “removal” figures. Thus, we focus on removals.

This blog post is a summary of the paper “Mass Deportations and the Future of Latino Politics,” presented at the 2014 meeting of the Western Political Science Association. The research was supported by the Russell Sage Foundation and Cornell University.

Michael Jones-Correa is a Professor of Government at Cornell University, Alex Street is a research fellow at the Max Planck Institute in Göttingen, Germany, and Chris Zepeda-Millán is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Loyola Marymount University.