It is well documented that anti-Latino rhetoric and policies by Republican candidates since the mid-1990s led Latino voters to abandon the GOP in favor of the Democratic Party (Bowler and Segura 2012). For example, research on California shows promotion of the anti-immigrant Prop 187 was directly tied to decreases in Republican partisanship among Latinos (Barreto and Woods 2005). President Obama’s victories in 2008 and 2012, won with overwhelming Latino support, have led many to conclude that Republicans have lost a generation or two of Latino voters. One conservative camp including the likes of Patrick Buchanan, contend that the only viable strategy for the GOP is to cast off Latino voters while doubling-down on white voters, a revival of Nixon’s Southern Strategy. Others, like Karl Rove, offer a less pessimistic assessment, and contend that the GOP is in a position to make inroads with Latino voters if the party and candidates change their rhetoric and policy positions on immigration. Whether Latinos are open or closed to GOP outreach efforts is based on whether one believes Latinos partisanship is fixed or flexible. Here we take a look at the empirical data, from a survey of nearly 6,000 Latino immigrants and find clear evidence that party identification among Latino non-citizens is largely non-partisan and undefined.

The nature of Latino partisanship — fixed or flexible– has been a long standing debate among scholars. Essentially, there are two dominant theories of partisanship; those who emphasize the importance early childhood socialization where partisan identities are inherited from one’s parents and remains stable through adulthood (Campbell et al 1960), and those who emphasize the importance of issues, candidates, and campaign dynamics which leads to greater partisan variability (Fiorina 1981). Although, much of the scholarship on partisanship comes down to a debate between those who emphasize long-term social forces and those who emphasize short-term considerations (Achen 1992); a significant limitation in this body of research is that the partisan attachments of immigrants and Latinos have largely been overlooked. Hence, the degree to which Latino partisanship is a stable or volatile across elections remains underexplored by academic researchers.

The handful of studies on Latino party identification tends to emphasize its variability across elections as a result of the candidate position-taking on key issues, and the fact that parental socialization of American politics is nonexistent for immigrants (Wong 2000; Alvarez and Bedolla 2003; Nicholson and Segura 2005; Uhlaner and Garcia 2005). A common understanding in the scholarly research on partisanship is that today’s immigrants do not have fixed or set party allegiances. There is no research to date that non-citizen immigrants have pre-existing party attachment that they take with to their naturalization ceremony. Rather, immigrants are seen as responsive to the political environment in which they find themselves and develop party attachment as they become citizens, register, and start voting.

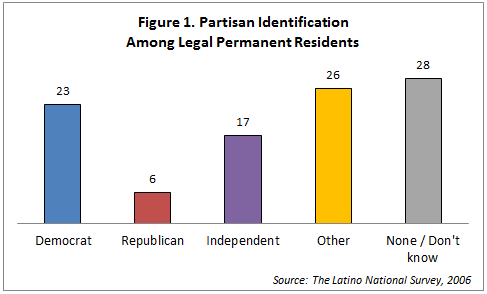

In fact, an empirical look at the data confirms this theory. Among Latinos who are Legal Permanent Residents (LPRs, immigrants eligible for US citizenship), 17% self-identify as Independents according to the 2006 Latino National Survey (see Figure 1). Even more significant is the fact that 28% eschew the Independent label and are best classified as “non-identifiers”. One quarter (26%) identify their party affiliation as simply “other” – rejecting both the Republican or Democratic Party. In other words, far from being solidly aligned with the Democratic Party, a total of 71% of Latino LPRs do not identify with either party.

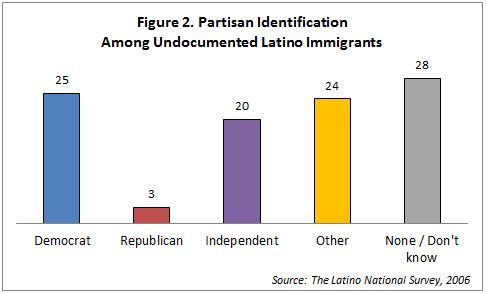

Of course, not all Latino immigrants are LPRs, most become naturalized American citizens, and some are in an undocumented status. One of the primary obstacles Republicans express for legalizing the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants is the belief that doing so will be a political windfall for the Democratic Party. The facts do not comport with this common misconception. Among Latino undocumented immigrants the Latino National Survey reports virtually the same patterns of partisan identification as legal permanent residents with only 1 in 4 identifying as Democrats. Instead, 72% of Latino undocumented immigrants have no party identification with the two major political parties. The reason is simple: undocumented immigrants are still learning the positions and orientations of the political parties, and develop their party orientation over time as they become green card holders and eventually naturalized citizens.

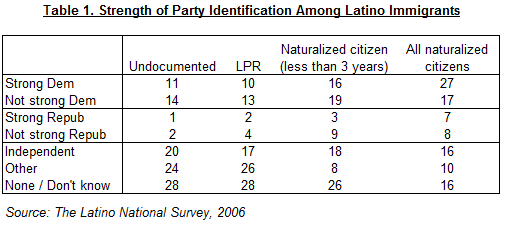

What’s more, even among the minority those who do pick Democrat or Republican, over half say their party attachment is “not too strong.” Out of every 100 Latino undocumented immigrants, just 11 identify as “Strong Democrats.” Likewise, among Latino legal residents, just 10 percent say they are “Strong Democrats” (see Table 1). Both parties must compete to win the votes of these new citizens and new voters.

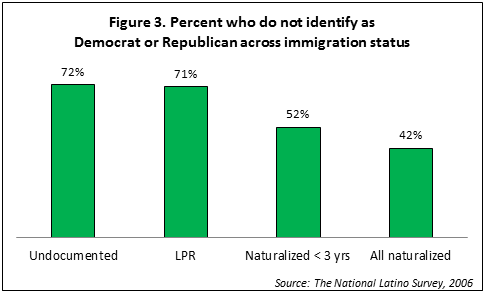

Finally, Figure 3 illustrates the degree of non-partisanship across four different types of Latino immigrants: (1) undocumented immigrants; (2) Legal Permanent Residents; (3) newly naturalized citizens (3 years or less); (4) and all naturalized immigrants.

More than seventy percent of undocumented (72%) and LPRs (71%) do not identify as Democrats or Republicans. Among immigrants naturalized 3 years or less, that figure declines to 52%, and declines even further, to 42% among all naturalized Latino United States citizens. In other words, as Latinos become citizens, the greater the likelihood they will select one of the two major parties. Right now, that preference tends to favor Democrats, but a change in GOP strategy could tilt that partisan direction in their favor. After all, far from being Democrats, the majority of Latino immigrants have yet to pick one of the two major parties.

Strategies either party may adopt to strengthen their position with the expanding Latino electorate should target Latino immigrants whose partisan preferences have yet to be formed. Policies and rhetoric, specifically directed and applicable to immigrants, will have a significant effect on partisan identification among naturalized voters. While parental socialization may be absent, political socialization forces are pervasive once immigrants settle in the United States. In fact, a consistent finding in the Latino politics literature is that identification with the Democratic Party increases with age and length of residency (Cain. Kiewiet and Uhlaner 1991; Wong 2000; Uhlaner and Garcia 2005). The findings in Table 1 are indicative of that trend.

Indeed, the GOP has a real opportunity to win the partisan hearts and minds of Latino immigrants, the data are clear on this proposition. However, if skeptics are unconvinced by the data, then perhaps history, in the form of Ronald Regan’s and George W. Bush’s campaigns, proves that Latino’s partisan hearts and minds are open to Republican messages as both won over 40% of the Latino vote during their campaigns for the presidency. Had Romney won a similar percentage in 2012, the presidency would have been within reach.

Note: The data analyzed here come the 2006 Latino National Survey, the largest political science study of Latinos and American politics. The survey was designed and implemented by a team of six principal investigators including Dr. Luis Fraga (Univ. of Washington), Dr. John Garcia (Univ. of Michigan), Dr. Rodney Hero (UC Berkeley), Dr. Michael Jones-Correa (Cornell), Dr. Valerie Martinez-Ebers (Univ. of North Texas), and Dr. Gary Segura (Stanford). The data are archived at ICPSR #20862

Scholarly References

Achen, Christopher H. 1992. “Breaking the Iron Triangle: Social Psychology, Demographic Variables and Linear Regression in Voting Research” Political Behavior 14: 195-211.

Alvarez, R. Michael and Lisa Garcia Bedolla. 2003. “The Foundations of Latino Voter Partisanship: Evidence from the 2000 Election” The Journal of Politics 65: 31-49.

Barreto, Matt A. and Nathan D. Woods. 2005. “ “The Anti-Latino Political Context and its Impact on GOP Detachment and Increasing Latino Voter Turnout in Los Angeles County.” In Gary Segura and Shawn Bowler (eds.) Diversity in Democracy: Minority Representation in the United States. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Bowler, Shaun and Gary M. Segura. 2012. The Future is Ours, Minority Politics, Political Behavior, and the Multiracial Era of American Politics. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press

Cain, Bruce E., D. Roderick Kiewiet and Carol J. Uhlaner. 1991. “The Acquisition of Partisanship by Latinos and Asian Americans” American Journal of Political Science 32: 390-422.

Campbell, Angus, Philip Converse, Warren Miller and Donald Stokes. 1960. The American Voter. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fiorina, Morris P. 1981. Retrospective Voting in American National Elections. 2nd ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Nicholson, Stephen P. and Gary M. Segura. 2005. “Issue Agendas and the Politics of Latino Partisan Identification” in Gary M. Segura and Shaun Bowler eds., Diversity in Democracy, Minority Representation in the United States. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

Uhlaner, Carol J. and F. Chris Garcia. 2005. “Learning Which Party Fits, Experience, Ethnic Identity, and the Demographic Foundations of Latino Party Identification” in Gary M. Segura and Shaun Bowler eds., Diversity in Democracy, Minority Representation in the United States. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

Wong, Janelle S. 2000. “The Effects of Age and Political Exposure on the Development of Party Identification Among Asian American and Latino Immigrants in the United States” Political Behavior 22: 341-371

The data are taken from the 2006 Latino National Survey (LNS), one of the largest and most trusted national surveys of the Latino population. The number of respondents who are foreign-born is 5,717. The survey instrument contained approximately 165 distinct items ranging from demographic descriptions to political attitudes and policy preferences, as well as a variety of social indicators and experiences. All interviewers were bilingual, English and Spanish. Respondents were greeted in both languages and were immediately offered the opportunity to interview in either language.