In a prior post I examined what occurred in the 24 Republican held tier one and tier two Latino Influence House Districts during the 2014 elections. My analysis revealed that while there were a number of potentially competitive districts, the Democrats’ inability to recruit and fund quality challengers resulted in a number of Republicans who narrowly won in 2012 being given passes in 2014. Without the emergence of quality challengers in these districts, Latinos and other pro-immigration reform voters were unable to hold House Republicans accountable for their failure to act on comprehensive immigration reform. Indeed, among these 24 districts, the Democrats were able to pick-up just two seats: an open seat in California (CA-31) and the 2nd district in Florida.

At the same time, what occurred in 2014 was consistent with how parties respond to an unfavorable macro political environment. If donors and party leaders perceive it will be a down year, they devote fewer resources to challenging vulnerable incumbents of the opposition party and more resources protecting their incumbents. This was certainly the case with the Democrats in 2014.

The opposite holds for the party that the macro environment favors such that their party’s leaders and donors seek to expand the number of districts in play through aggressive recruitment and strategic allocation of campaign resources. Because many of the party’s most vulnerable incumbents are not being seriously challenged, the party is also able to provide these challengers with more resources. The spending by Super PACs and other outside entities further enhance these patterns.

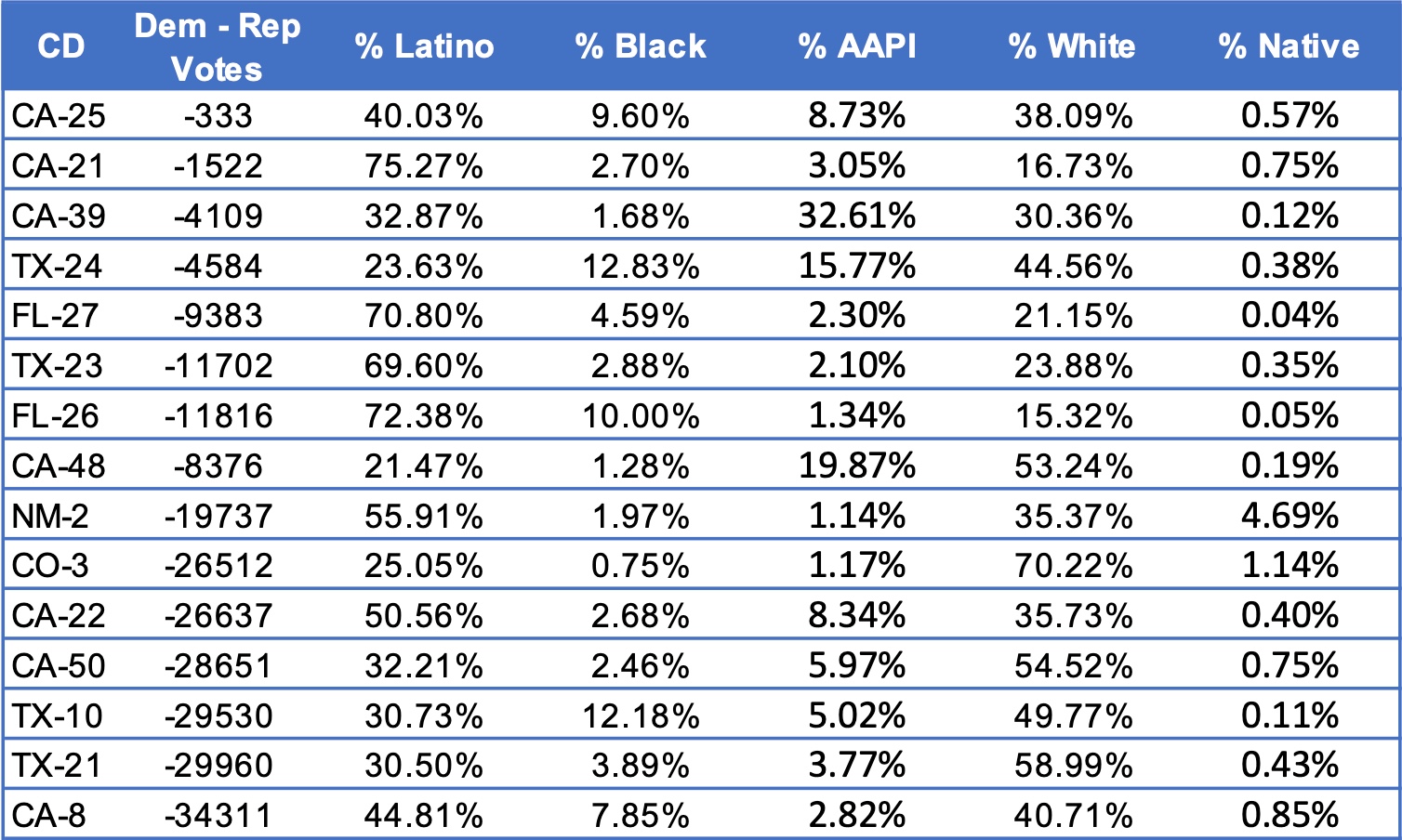

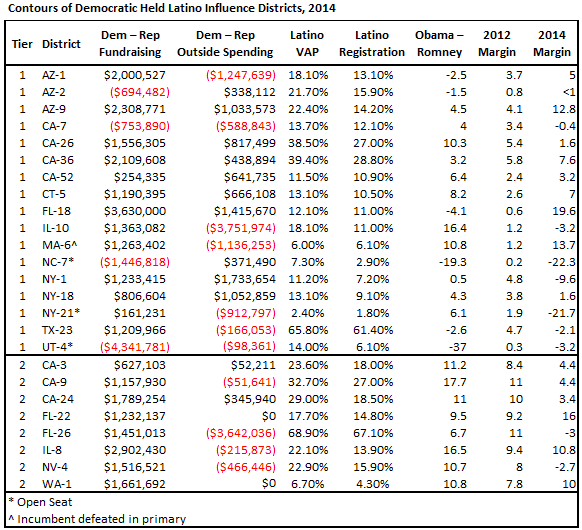

The data presented in the table below suggest such effects. Specifically, these tables summarize the 25 Democratic held tier one and tier two Latino Influence districts’ demography (Latino VAP and Latino share of registered voters) and competitiveness (2012 House and presidential margin of victory); party differences in candidate fundraising and outside spending; and the 2014 margin of victory.[i]

Excluding the three Democratic open seats (NC-7, NY-21, and UT-4, all of which were won by Republicans), all Democratic incumbents outraised their Republican challengers except for Ron Barber in AZ-2. Seth Moulton (MA-6), who defeated Democratic incumbent John Tierney in the primary, also had a substantial fundraising advantage over his Republican general election opponent. Collectively, the Democrats running in the Democratic tier one and tier two districts raised $72.2 million as compared to $47.8 million for the Republican candidates (a 1.5 to 1 ratio) competing in these districts. However, the Republican fundraising disadvantage was offset, in part, by spending by outside groups either bolstering Republicans or attacking Democrats. Indeed, the Republican candidates in these districts received $3.3 million more in outside spending than the Democratic candidates.

Yet, despite the Democrats’ emphasis on incumbent protection, Republicans were able to flip 10 of the 25 Democratic held tier one and tier two Latino Influence districts. Democratic losses in these districts account for 10 of the 16 seats the GOP picked up in 2014 and in just nine of these districts did the Democrats increase their margin of victory as compared to 2012 (in the other six districts the Democrats won, the margin of victory decreased as compared to 2012).

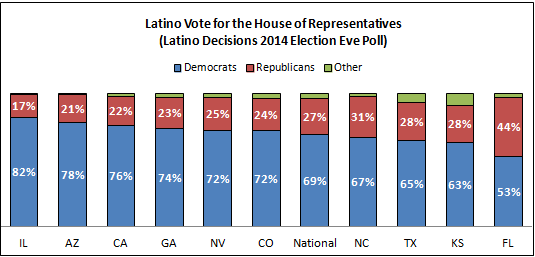

Although the 2012 and 2014 Latino Decisions Election Eve Polls did not disaggregate results for specific House districts (due to small samples in each district), as the figure below summarizes, nationally Latino support for Democratic House candidates decreased from 77% in 2012 to 69% in 2014, while the Republican share increased from 23% to 27%. Certainly, some of this drop-off in Democratic support stems from differences in the composition of the 2012 and 2014 Latino electorates. Typically, the midterm electorate is older and draws more heavily from higher socio-economic voters; factors that correlate with greater support for the GOP.

However, equally important to consider are the differences between the “Latino VAP” and “Latino Registration Share” columns in the above table. In only three (CA-52, NY-21, MA-6) of the 25 districts was the Latino registration share within plus or minus one percentage point of the share of Latinos in the district who were of voting age. Moreover, in nine of the 10 seats that switched from Democratic to Republican control in 2014 (the only exception is the heavily Latino FL-26), the difference between “Latino VAP” and “Latino Registration Share” is greater than the 2014 margin of victory for the Republican candidate. The most obvious example of this is Arizona’s 2nd district where Democratic incumbent Ron Barber lost to Republican Martha McSally by 161 votes. The district has a Latino voting age population of nearly 22%, but Latinos constitute less than 16% of registered voters.

Taken in total, the patterns in the tier one and tier two Latino Influence districts in 2014 are consistent with the “self-fulfilling” prophecy hypothesis linking expectations about the macro-political environment to decisions in individual districts. Fearing a bad electoral environment, the Democrats emphasized incumbent protection over candidate recruitment, while the Republicans did just the opposite. Having stronger challengers allowed Republicans to raise sufficient resources and with the assistance of outside groups overcome the fundraising strength of Democratic candidates running in the Democratic held tier one and tier two districts.

______

[i] Data for the “Rep – Dem Fundraising” and the “Rep – Dem Outside Spending” columns of are from OpenSecrets.org. The “Latino VAP” column uses 2010 U.S. Census data summarizing the Latino share of the voting age population in each House district, while the “Latino Registration Share” column uses data from L2 Votermapping capturing the Latino share of registered voters in each district. Data for the “2012 margin” and “2014 Margin” columns are from the Associated Press and data for the “Obama – Romney” column are from Daily Kos.

David Damore is a Senior Analyst at Latino Decisions. He is Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and a Senior Nonresident Fellow in the Brookings Institution’s Governance Studies Program.