Reports that the House Republican leadership will not consider immigration legislation during the present Congress once again raises the prospects that President Obama will take executive action on immigration. Recent polling conducted by Latino Decisions for the Center for American Progress Action Fund suggests that executive action on immigration could help to offset some of the headwinds that Democratic candidates are facing as the 2014 midterm elections approach.

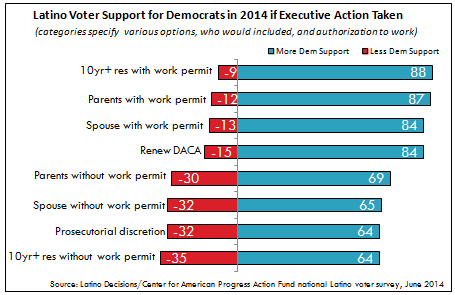

The poll of 800 Latino voters finds broad support for many executive policy options including granting temporary work permits and stopping deportations of unauthorized immigrants without criminal records (summary results here). More significant for the Democrats’ near term prospects, the poll finds sharp increases in enthusiasm for the Democrats if the president acts.

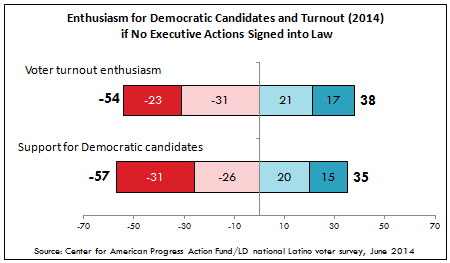

However, if executive action does not materialize, most Latino voters indicate they will be less enthusiastic about participating in November, and less enthusiastic about supporting Democrats.

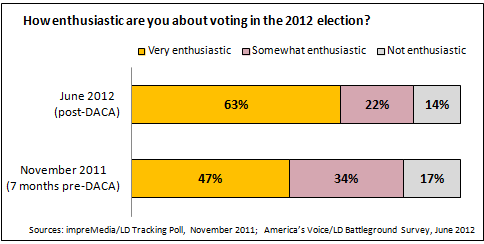

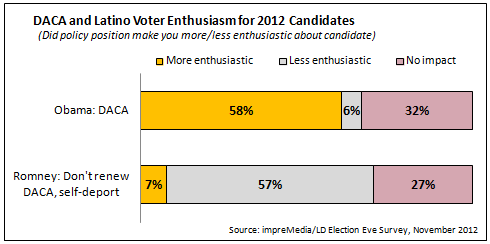

In this respect, the results suggest effects similar to those stemming from President Obama’s use of executive authority in June 2012 to create the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. After the DACA announcement, Latino Decisions polling found upticks in Latino enthusiasm for participating in the 2012 election, and favorability for Democrats.

Indeed, if President Obama had not directed the Department of Homeland Security to defer deportation of some undocumented youth who came to the United States as children, it is difficult to think that Latino voters would have cast their ballots so overwhelmingly for Democratic candidates.

Prior to the DACA announcement, the immigration narrative focused on record deportations on Obama’s watch, and the president’s failure to initiate immigration legislation in his first term. DACA, coupled with Mitt Romney’s pronouncements about self-deportation, boosted Latino engagement and continued the movement of Latino voters to the Democratic Party.

Of course, there are a number of differences between 2012 and 2014. Most obviously, while deportations remain salient and the influx of Central American children at the border poses a humanitarian crisis, the larger policy environment has changed.

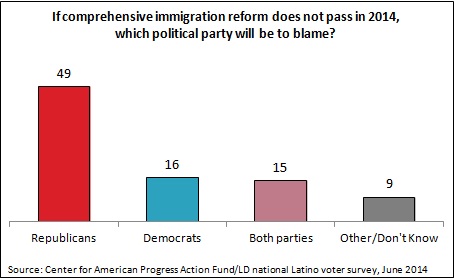

Last June the Senate passed S.744, the Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act, and the president indicated he would sign into law. The Senate bill created a benchmark of what comprehensive immigration reform legislation should entail both in terms of policy, and what is expected by and acceptable to the vast majority of Americans. Moving legislation this far through the process and still coming up short solidifies the House Republicans’ culpability in failing to deliver on the Latino electorate’s most pressing policy priority.

This set of events echoes another pivotal moment in immigration politics: the failed efforts of 2006 and 2007. At the time, there was a good deal of finger-pointing about which party was responsible for derailing reform, but there was no such equivocation among Latino voters. Since that time, Latinos have increasingly and overwhelmingly favored Democratic candidates in each ensuing election.

Most notably, the shift in Latino support from Bush to Romney (40% to 23%) represents the largest inter-election movement of any racial or ethnic group between 2004 and 2012. The impact of this shift takes on even greater importance given that Latinos cast 3.6 million more votes in 2012 compared to 2004.

The political scenario in the upcoming midterm remains quite different from 2012. President Obama will not be on the ballot, and except for Colorado’s U.S. Senate race, there are no statewide federal races where Latino voters are positioned to be decisive. While Democrats could frame any executive action President Obama takes as a necessary response to Republican recalcitrant to gain further ownership of the immigration issue, the political benefits the party’s candidates may reap are likely to be limited to the House of Representatives.

In a follow-up analysis, I will examine the most vulnerable Democratic seats of this cycle – the six districts Mitt Romney carried in 2012 – and assess how executive action might play in these districts.

David Damore is a senior analyst at Latino Decisions, Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Nevada Las Vegas, and a Senior Nonresident Fellow in the Brookings Institution’s Governance Studies Program.