A contemporary feature of global migration is the ability for immigrants to maintain transnational ties with their countries of origin while residing in the United States. These ties can vary in kind and strength and range from feelings of nostalgia to actively participating politically, socially, and/or economically abroad. The rise of transnational ties and dual citizenship has led some to conclude that today’s immigrants have divided loyalties and no longer build the same emotional attachments to the United States. Writing for the Center for Immigration Studies, Professor Stanley Renshon summarizes this sentiment by noting, “Dual citizens are those who make an affirmative effort to retain their cultural, political, economic, and emotional ties to their homeland. They are less likely to see themselves primarily or exclusively as Americans. They are more likely to remain oriented to the language, customs, and outlook of their home country. And they are more likely to try and instill in their children an informational and emotional connection to the home country. They are also more likely to have a merely instrumental attachment to the United States” (Hyphenation vs Dual Citizenship, Jan 16, 2011). Prominent critics like Arthur Schlesinger, Patrick Buchanan, Tom Tancredo, and the late Samuel Huntington share Renshon’s views.

Do transnational ties, including dual citizenship, impede the assimilation process by creating dual loyalties? Do they undermine American national identity by fostering ambivalent feelings toward the U.S. among immigrants? A review of research published in peer-reviewed scholarly journals shows that the majority find that transnational ties quicken the assimilation process, which in turn strengthen immigrant ties and feelings toward America (e.g., Jones-Correa 1998, 2001; Guarnizo, Portes and Haller 2003; Pantoja 2005; and Ramakrishnan 2005). While I cannot summarize all of studies on this subject, I will look at data from the Latino National Survey, the largest national survey on Latinos, to illustrate how transnational ties quicken the naturalization process and induce civic engagement among immigrants (for a detailed analysis see Gershon and Pantoja 2013).

The pursuit of U.S. citizenship and participation in the American politics process are two visible examples of immigrant incorporation. Delays in these activities demonstrate an absence of incorporation and have the potential to weaken the American democratic process if large numbers remain unengaged. What effect do transnational ties have on naturalization and political participation?

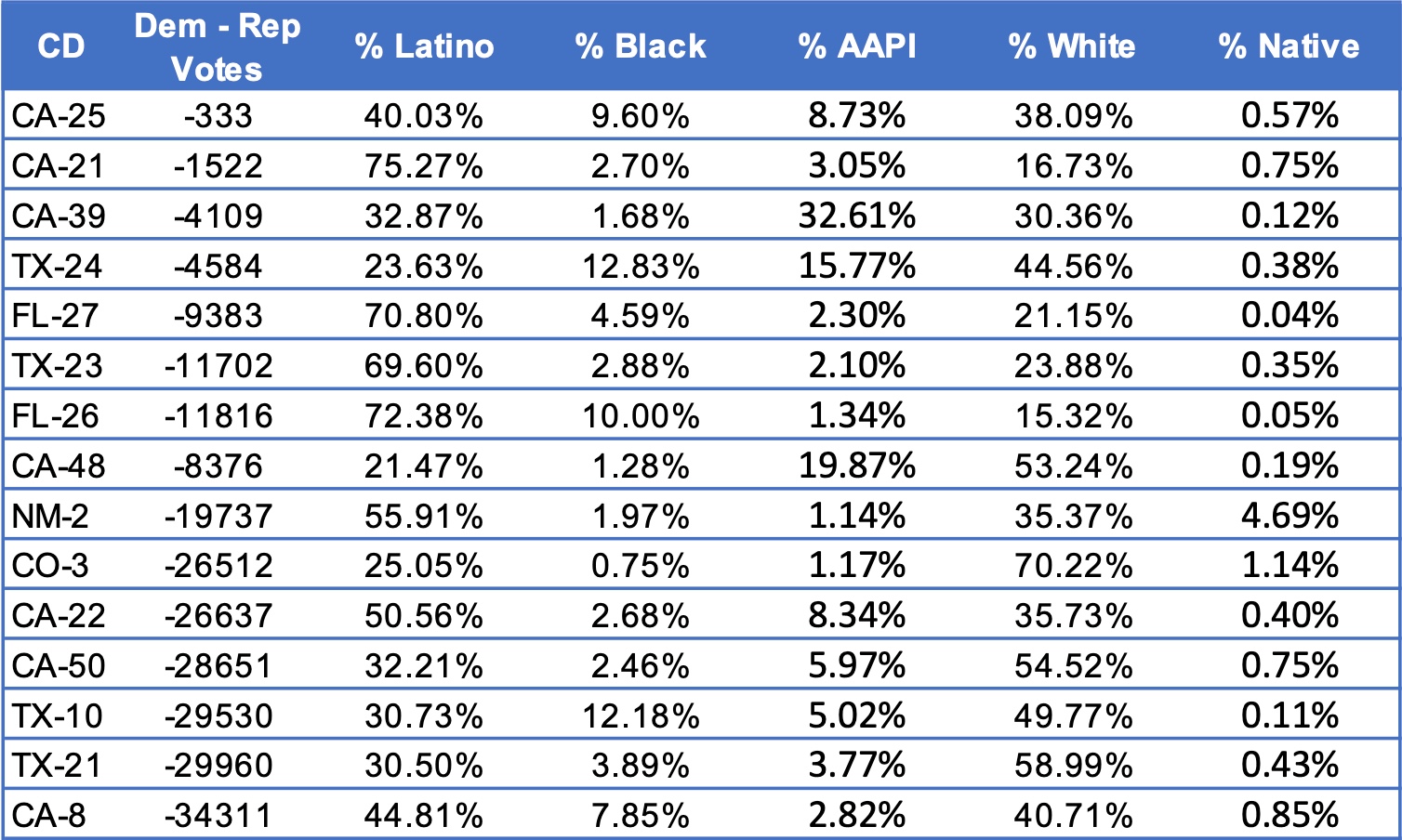

I first consider the acquisition of U.S. citizenship. As a proxy of transnational ties, I use a question that captures the frequency of visits to the country of ancestry. A simple comparison of the number of visits abroad and the acquisition of U.S. citizenship among Latino immigrants (Table 1) shows that high frequency of visits does not affect the acquisition of citizenship. In fact, it is U.S. citizens who seem to have higher levels of transnational ties. This finding is contrary to those who argue transnational ties impede the incorporation process through delays in naturalization.

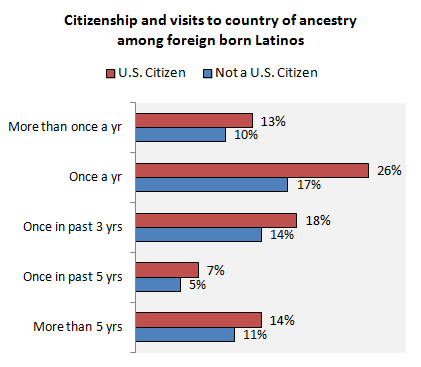

How about the impact of transnational ties on political participation? Using the same proxy for transnational ties, I cross-tabulate those responses with the following question, “Have you ever tried to get government officials to pay attention to something that concerned you, either by calling, writing a latter, or going to a meeting?” Table 2 shows that respondents who have higher levels of transnational ties also have higher levels of political participation. While the participation gap across the levels of transnational activities is small, they nonetheless show that transnational ties are not an impediment to participating in U.S. politics and may in fact promote civic engagement.

Critics of contemporary immigration contend that today’s newcomers are different from previous waves because of transnational ties with their countries of ancestries. It is alleged that these ties lead to divided loyalties, impede the incorporation process, and undermine American identity and democracy. A review of the scholarly literature shows that this assumption is misguided. Transnational ties are on the rise, but rather than impeding the incorporation process, they quicken it. Tables 1 and 2 illustrate this point with data from the Latino National Survey. Immigrants who are transnationally connected are not on the fringes of American civic life, but well-integrated into the polity as naturalized citizens and political participants. The acquisition of U.S. citizenship and political participation strengthens ties to America by fostering feelings of patriotism, tolerance, community, and other core American values among immigrants. In short, transnational ties are good for immigrants and America.

Adrian Pantoja is professor political studies at Pitzer College, and a senior analyst at Latino Decisions.

References

Gershon, Sarah Allen, Adrian D. Pantoja. 2013. “Pessimists, Optimists, and Skeptics: The Consequences of Transnational Ties for Latino Immigrant Naturalization” Social Science Quarterly online: 22 May 2013.

Guarnizo, Luis Eduardo, Alejandro Portes and William Haller. 2003. “Assimilation and Transnationalism: Determinants of Transnational Political Action among Contemporary Migrants” American Journal of Sociology 108: 1211-48.

Jones-Correa, Michael. 1998. Between Two Nations, The Political Predicament of Latinos in New York City. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Jones-Correa, Michael. 2001. “Under Two Flags: Dual Nationality in Latin America and Its Consequences for Naturalization in the United States.” International Migration Review 35: 997-1029.

Pantoja, Adrian. 2005. “Transnational Ties and Immigrant Political Incorporation: The Case of Dominicans in Washington Heights, New York” International Migration 43:123-46.

Ramakrishnan, Karthick S. 2005. Democracy in Immigrant America, Changing Demographics and Political Participation. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.