By Francisco Pedraza, Texas A&M University

In his most recent statement on immigration, a speech in May of 2011 in El Paso, President Obama framed immigration in economic terms and he did this in two ways. First, President Obama pitched immigration as part of a broader strategy for the U.S. to remain competitive in a global marketplace. Second, President Obama cast the domestic debate in economic terms by suggesting a price for immigration reform. I will leave it to others to comment on whether this framing strategy is likely to pay off in terms of policy output. What I look at here is how the language of “price of immigration reform” is playing out in the policy attitudes among Latinos.

The price of immigration reform, as outlined by President Obama, should be paid by the government, business and immigrants themselves. In order to signal a credible commitment to reform, President Obama doubled down on the government’s payment towards border security and enforcement, and business is expected to pay in terms of accountability in hiring practices. For undocumented immigrants the price comes in the form of restrictions to live continuously in the U.S., learn English, return temporarily to country of origin, pay old taxes and pay a fine. Are Latinos willing to pay the price of immigration reform?

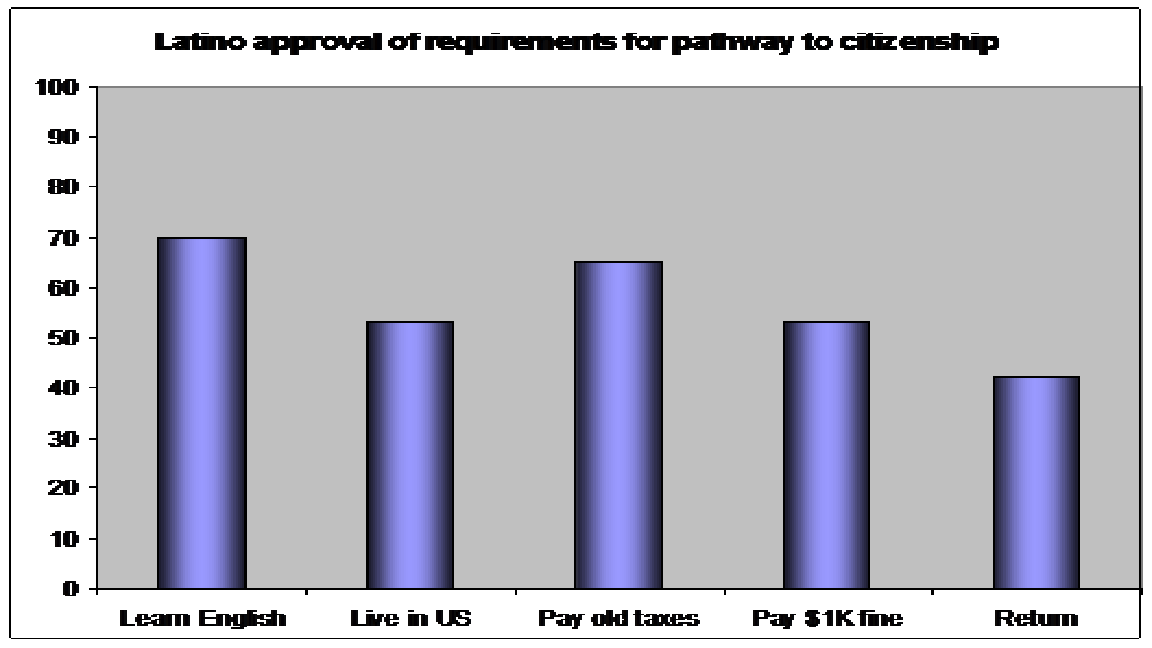

In the June 2011 installment of Latino Decisions tracking poll, Latino registered voters were asked whether they would support or oppose a series of components as the price for a policy providing an eventual pathway to citizenship. With the exception of returning to country of origin, a majority of Latinos approve of requirements proposed as the price that immigrants pay for a pathway to citizenship. We can think of learning English (70% approval) and having lived continuously in the US for two years as payment that immigrants have already made or are making. Majority approval of requirements to pay old taxes (though many undocumented have probably paid in a fair share already under a different name and tax identification number) and a $1000 fine is interesting because this entails a price to be paid after enactment of reform. Some may not be surprised by the relatively low 42% Latino approval for returning to country of origin. However, the monetary cost of safe entry into the US without documents is exorbitant, and probably more than the proposed $1000 fine. Calculate in considerations of family separation, job loss, and the widespread knowledge that it takes years to regularize one’s status, and 42% approval of returning to country of origin no longer seems low. In the aggregate, these data suggest relatively high level of Latino approval for the various components. Insofar as Latinos are implicated in the immigration debate as immigrants it seems a key constituency is willing to pay the price for a pathway to citizenship.

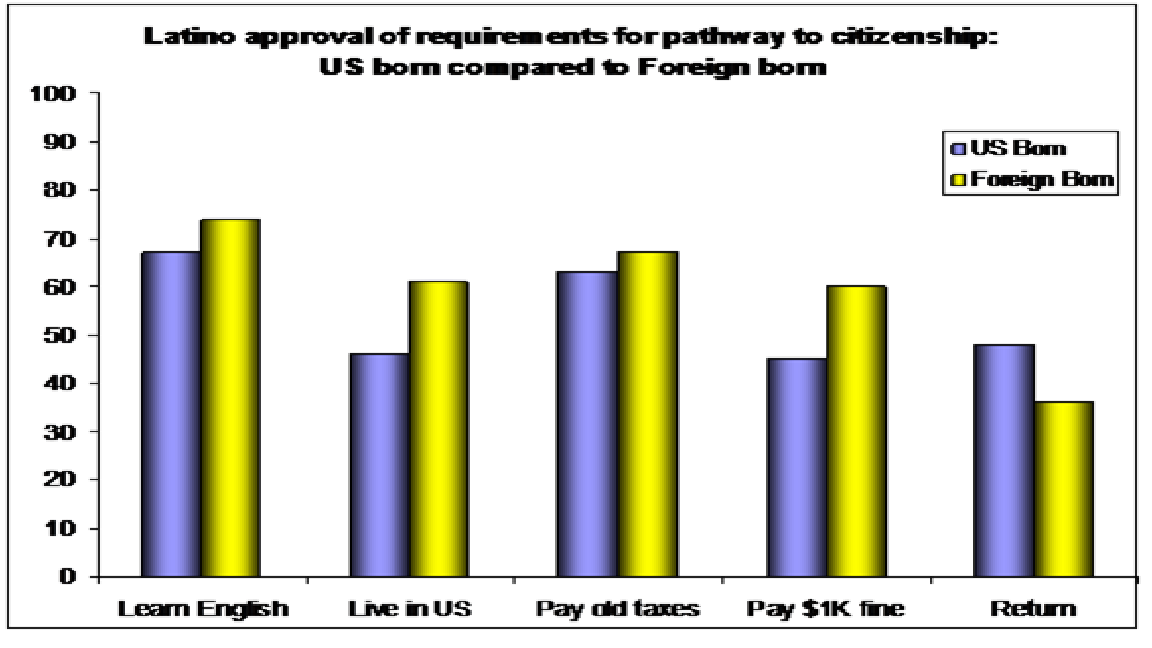

Of course, Latinos are a very diverse community. It is reasonable to expect that differences in the willingness to pay a price for immigration reform vary depending on whether one shoulders the burden of that cost directly. Latino Decisions Tracking Poll is of registered voters, so there are no Latinos who are undocumented represented in these data. An alternative distinction that is available in the data is US nativity. The figure below compares the attitudes of foreign born and US born Latino voters. There is little to no variability with respect to learning English, the most widely approved proposed requisite, or returning to country of origin, the most widely disapproved. However, Latinos born outside of the US express greater approval for requirements to live two years in the US, pay old taxes and pay a $1000 fine.

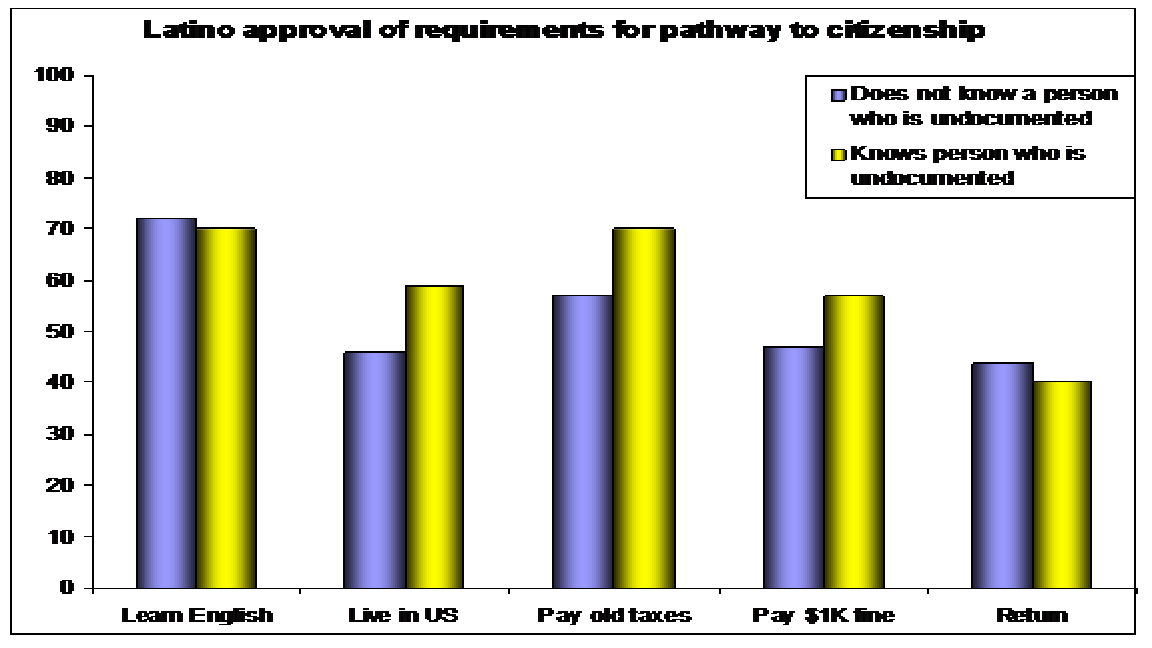

In an earlier post Professor Gabriel Sanchez presented an analysis of Latino support for immigration policy and argued that having a personal connection to undocumented immigrants is a key explanatory factor. A full 53% of Latino voters said that they know someone who is undocumented. Are Latinos with a personal connection to an undocumented immigrant willing to pay the price for immigration reform?

The figure below compares approval by personal connection to an undocumented immigrant. The pattern that emerges is consistent with the argument advanced by Professor Sanchez, and is similar to that shown above regarding the distinction between the foreign born and US born Latino voters. Latinos who personally know someone who is undocumented express greater approval for requirements to live two years in the US, pay old taxes and pay a $1000 fine. These are the costs that would be paid should immigration reform be enacted with these measures, and Latino voters with a personal connection say they approve the cost to ensure a pathway to citizenship.

While Latino voters are willing to approve that immigrants pay a price for a pathway to citizenship, there are bounds to what price is acceptable. We might anticipate that Latinos who immigrated or who have a personal connection to the immigration experience are the most resistant to a policy strategy of inclusion through exclusion. However, even those who are not personally connected to someone who is undocumented register a similar level of approval regarding returning to country of origin (44%), a four point difference from the 40% who are connected.

For now immigration is not on the policy agenda, but in preparation for the next round of debate policy makers and influence leaders should understand that the ties that bind many Latinos, though certainly not all, place limits on the approval of the price that immigrants pay for a pathway to citizenship. We now have a sophisticated sociological and anthropological understanding that the decision-making behind emigration is very family-oriented and relies heavily on social networks of extended family, friends and acquaintances. It is those connections that make some sacrifices, or `prices’ to use the language of President Obama, more or less palatable

Francisco I. Pedraza, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Texas A&M University, and a collaborator on the April 2009 Latino Decisions 100 Days Poll, as well as the current 2010 tracking poll