According to polling data from the Field Poll, after winning the presidential election in 1980, California native Ronald Reagan raised his share of the Latino vote from 35 percent to 45 percent in 1984 while carrying 59 percent of the entire state. Republicans went on to win the Golden state again in 1988. Since then, three things have happened: first the Latino share of all voters in California started growing noticeably, and second: California Republicans embarked on an anti-immigrant agenda that ended up alienating Latino voters and driving them into the open arms of the Democratic Party, and third: Republicans have permanently written off 55 electoral college votes – or approximately 20% of the amount needed to reach 270.

As the Latino voter population grows across other states, and a rigorous debate unfolds about immigration reform, we take this opportunity to revisit lessons learned from California. How did California go from a Republican stronghold to a Democratic lock? The answer is clear – anti-immigrant policy and a frustrated and mobilized Latino vote.

It is now well known in the political science research world and the real world of campaigns and politics that the mid-1990s Pete Wilson era of California Republicanism was a historic turning point in the state’s politics. The infamous anti-immigrant ballot measure, Prop. 187 was championed by then Governor Pete Wilson in his re-election bid and resulted in a significant backlash, and political mobilization among Latino voters in California. Following Prop. 187 were additional anti-immigrant measures such as Prop. 209 and Prop. 227 to outlaw affirmative action and bilingual education.

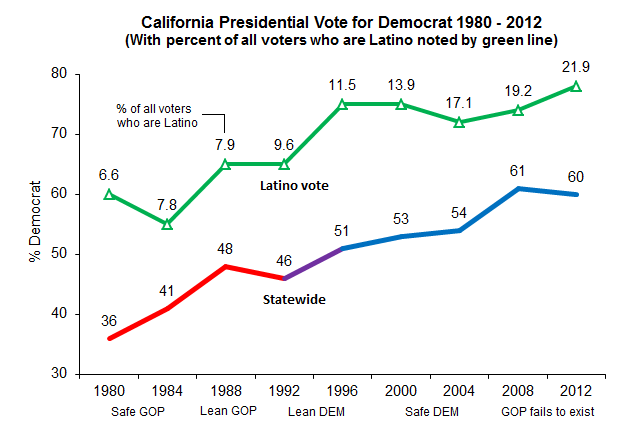

In 1996 when Latinos first comprised more than 10 percent of the state electorate and Latino partisanship had grown dramatically to over 70 percent Democratic, it is no coincidence that California became an easy win for the Democrats. As Latino voter registration grew in the mid-to-late 1990s, the Republican Party continued to emphasize anti-immigrant ballot measures that lead new Latino registrants to check the “Democrat” box on their registration cards. This trend has been clearly documented in political science research (see, Segura, Falcon and Pachon 1999; Ramírez 2002; Barreto and Woods 2005; Barreto, Ramírez, and Woods 2005). In an analysis of voter registration records in Los AngelesCounty between 1992 and 1998, Barreto and Woods (2005) found that just ten percent of new Latino registrants affiliated with the Republican Party as a direct result of the three so-called “anti-Latino” propositions in California. New Latino citizens were flooding the voter rolls in 1996, 1998 and 2000 and they were identifying as Democrat by a nearly 6-to-1 margin. And not just party registration, but the anti-Latino initiatives motivated many new Latinos to vote. Pantoja, Ramírez, and Segura (2001) found that Latinos who naturalized and registered to vote during the 1990s were significantly more likely to turnout and vote. Likewise, Barreto, Ramírez and Woods (2005) foundd the best predictor of voter turnout in 1996 and 2000 was whether or not Latinos were newly registered following Prop. 187. The overall result then was more Latinos registering and more Latinos voting as Democrats than in previous years.

However, the 2000 election suggested that the anti-Latino era might be over. Republican presidential candidate George W. Bush used his closeness and understanding of Latino voters in Texas to rally support for the Republican ticket in the Latino community—quite the opposite of the Republican strategy during California Governor Pete Wilson’s administration from 1990-1998 (Nuño 2007). Even as Bush attempted to introduce a new compassionate face to the Republican Party, the Republican Party label maintained an image problem with California Latino voters.

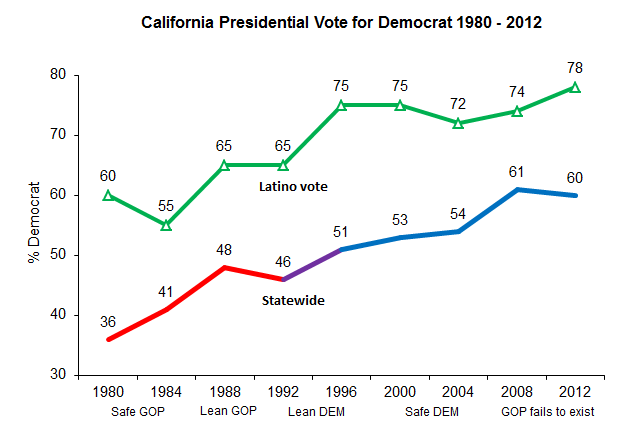

A survey conducted by the Tomás Rivera Policy Institute during the 2000 election revealed that 53 percent of Latino voters in California still associated the Republican Party with former Governor Pete Wilson, a chief proponent of the anti-immigrant Proposition 187 (TRPI 2000). Ten years later when Jerry Brown squared off against Meg Whitman for governor in 2010, 80 percent of Latino voters said they were very or somewhat concerned that Whitman had appointed Pete Wilson as a campaign co-chair — 12 years after he had left office! The result of Pete Wilson and Prop. 187 was a lasting legacy of strong support for Democratic candidates in California elections. The two figures below illustrate that as the Latino vote grew in influence, California became a more Democratic state. Most notably, the Latino vote became 10 to 13 percent more Democratic following the anti-immigrant policies endorsed by the GOP in 1994. In 1992 Democrats won 65 percent of the Latino vote, in 1996 Democrats won 75 percent of the Latino vote and by 2012 they were winning 78 percent of the Latino vote.

In addition to voting in presidential elections, Latinos in California have also become consistent Democratic voters in other statewide elections since the Reagan era. Statewide results indicate that Latinos voted two-to-one on average in support of Democratic candidates for Governor and U.S. Senate for every election between 1992 and 2002 (Barreto and Ramírez in 2004). While some may view the 2003 Gubernatorial Recall election as a potential shift away from the Democratic Party (Marinucci 2003), most analysis now concurs that the circumstances and context of this election were so unique that inferring trends from the 2003 Recall election is not valid, and further that the Republican surge was not long lasting (Kousser 2006). However, the Recall election does highlight just how important Latino voters are to the Democratic Party in California; in part due to the approximately ten-point drop in Latino support rates for Democratic candidates, Democratic Governor Gray Davis was recalled from office and replaced with Republican candidate Arnold Schwarzenegger (DeSipio and Masuoka 2006). Had Latinos turned out at just slightly greater rates, and voted at their average support rate for the Democratic candidates, Davis would not have been recalled in 2003. While the peculiarities of the 2003 Recall election are unlikely to ever be reproduced in a national presidential election, the outcome reveals that Latinos are a key component to Republican success in California.

Table 1 reports population growth and voter registration growth in California from 1994 to 2004 – the most relevant political years for “lessons learned” – broken down by racial and ethnic group. While overall the state grew by nearly 15 percent (or 4.6 million people), it was almost entirely driven by Latino and Asian-American growth. Similarly, Latinos and Asian Americans drove voter registration growth in the Golden State. Between 1994 and 2004, the state of California added an estimated 1.8 million new registered voters, of which 66 percent were Latino and 23 percent were Asian, leaving just 11 percent of new voters that were either White or Black.

Looking back to the mid-1990s and early 2000s in California politics provides many clear lessons for the Republican Party today. The California in 2012 that delivered 60 percent of the vote to Obama did not get there by accident. It was not that long ago that California was a safe state for Republican presidential candidates. The data and story that we review here remind us of the importance of the immigration issue, against the backdrop of a burgeoning Latino electorate. What California Republicans did in 1994-1998 effectively doomed their chances in any future state elections. Today other states such as Arizona, Texas, or even Virginia and North Carolina face their own immigration politics and a fast growing Latino electorate. Already the lessons of California appear to be well lived in neighboring Nevada where Sharron Angle’s anti-immigrant bid for the U.S. Senate in 2010 resulted in a similar outcome to Californias. The question is whether or not the Republican Party in other critical states, or nationally, wants to remain politically viable. Not just in 2014, but in 2016, 2020, and 2024, as the name Pete Wilson still lives on in infamy among Latino voters in California in 2013.

– – – –

Matt A. Barreto, Ph.D. is co-founder of Latino Decisions, and Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Washington. Ricardo Ramirez, Ph.D. is Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame. Combined, Barreto and Ramirez have authored more than 50 academic journal articles and three books on the subject of Latino politics, immigrant politics and racial and ethnic politics.