By Rogelio Sáenz

Last month I prepared a research brief overviewing the COVID-19 cases and deaths among Latinos.1 I showed that Latinos were largely overrepresented among persons who had contracted the virus across states, but were widely underrepresented among people who had lost their lives to COVID-19. I demonstrated that the latter was due principally to the youthfulness of the Latino population with the largest share of Latinos being in the younger age groups where the probabilities of death from the virus are relatively low.

A lot has happened since I prepared the initial report. For example, over the last month, states have increasingly been opening up for business. In addition, while many people continue to shelter-in-place, many others are out and about. Furthermore, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been three brutal murders of African Americans, with the latest—the murder of George Floyd at the knee of a white policeman—leading to massive demonstrations across the country and abroad. Finally, there have been significant changes in the prevalence of cases and deaths from the virus among Latinos over the last month, as the report describes below.

This data analysis is based on COVID-19 cases and deaths in which the identity of Latinos is known. As such, cases and deaths in which Latino identity is not known are not included in the analysis presented here. As opposed to the previous report in which I compiled the data from the COVID-19 data portals across states, I draw now on data compiled by the COVID-19 Tracking Project.2 The data used represent cases and deaths up to between May 18 to May 27 across states. In the analysis presented below, I compute ratios based on dividing the percentage of cases (or deaths) that are Latino in a given state by the percentage of the state’s population that is Latino. Ratios above 1.0 indicate that Latinos are overrepresented, while those below 1.0 indicate that Latinos are underrepresented.

COVID-19 Infections among Latinos Continue to Increase

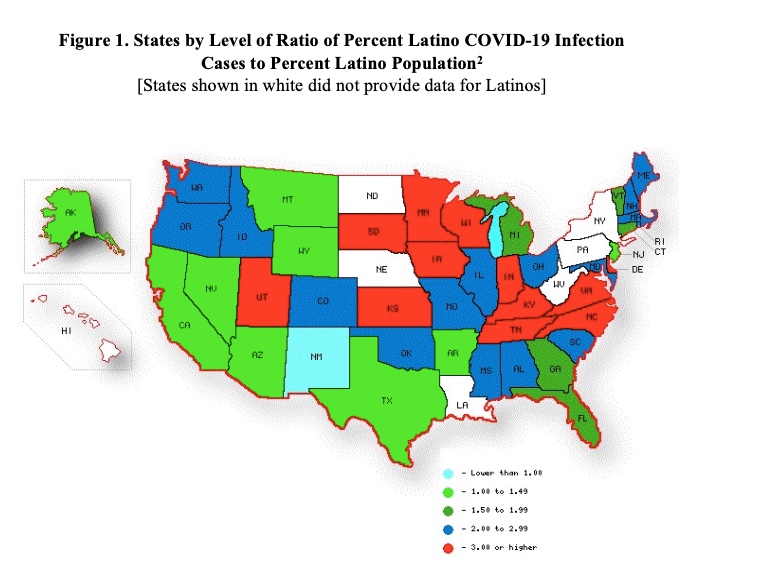

Last month I observed that Latinos were overwhelmingly overrepresented among people infected with the COVID-19 virus in 29 of the 35 states that provided data for Latinos.1 Things have gotten worse over the last month. Latinos are now overrepresented among persons who have caught the virus in 43 of the 44 states that provide information on Latinos, the exception being New Mexico where Latinos account for 49% of the state’s population but only 24% of COVID-19 cases. Figure 1 shows that distribution of states on the basis of the ratio between the percentage of Latinos among the infected relative to their share in the population. Latinos are twice as likely or more to be among COVID-19 cases than in the overall population in 29 of the 44 states. Of these 29 states, 21 have seen virus outbreaks in meatpacking operations, an industry where Latinos are disproportionately part of the workforce.3

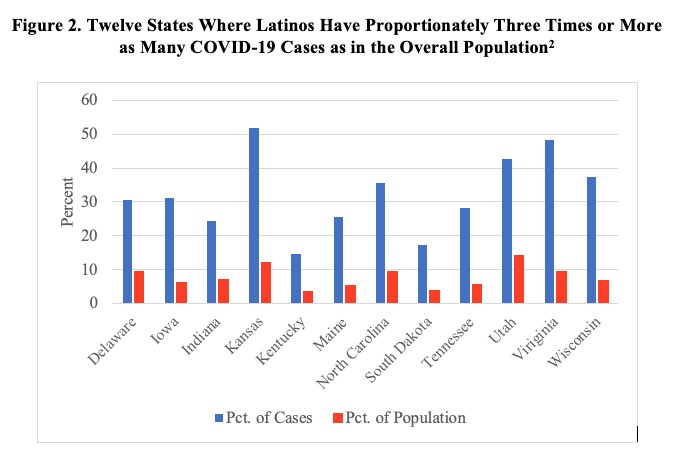

Figure 2 highlights the twelve states in which Latinos are three times as likely to be among persons who have caught the virus relative to their overall presence in the population. Aside from Utah, the other eleven states have sustained COVID-19 outbreaks in meatpacking operations.3 In Kansas, despite Latinos constituting only 12% of the state’s population, they account for more than half (52%) of persons who have contracted the virus. The ratio of the percentage of cases to the percentage of the population are 5.0 or higher in four states: Wisconsin (37.4% of cases are Latino versus 6.9% of population), Iowa (31.3% versus 6.1%), Tennessee (28.2% versus 5.5%), and Virginia (48.4% versus 9.6%).

Rising COVID-19 Deaths among Latinos

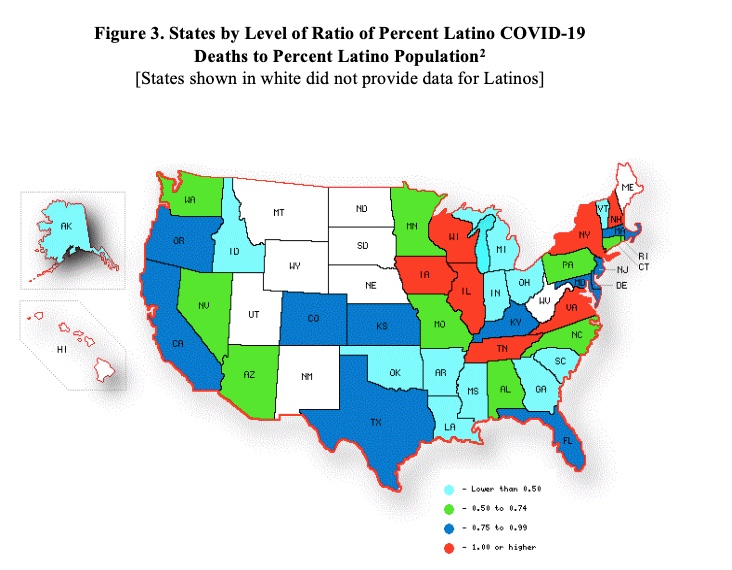

Last month, I observed that Latinos were overrepresented among people succumbing to the COVID-19 virus only in the state of New York, at that time excluding New York City.1 A month later, although the Latinos are largely underrepresented among COVID-fatalities in 34 of the 41 states that provide such data for Latinos, the number where Latinos are evenly represented or overrepresented among the dead has risen from one to seven (Figure 3). Of the seven, Latinos are actually more likely to be among the deceased than their share in the population in six states: New York (26.1% of COVID-19 fatalities versus 19.2% of the population), Wisconsin (8.9% versus 6.9%), Tennessee (6.6% versus 5.5%), Virginia (11.1% versus 9.6%), Illinois (19.8% versus 17.3%), and Iowa (6.7% versus 6.1%). In New Hampshire, Latinos represent 3.9% of the state’s COVID-19 cases and overall inhabitants.

What makes the growing number of states where Latinos are overrepresented among COVID-19 fatalities particularly troublesome is that Latinos are overall pretty young, concentrated in ages where the chances of dying from the virus are relatively low. Aside from New York where approximately one-tenth of the Latinos are 65 or older, the elderly make up only a handful of Latinos in the other five states where Latinos are overrepresented among the dead: Illinois, 6.1%; Virginia, 5.0%; Iowa, 3.6%; Tennessee, 3.5%; and Wisconsin, 3.5%.

In the research brief from last month, I showed that the underrepresentation of Latinos among the deceased from COVID-19 is due to the youthfulness of the Latino population.1 I demonstrated that in the limited number of geographic areas where age-specific COVID-19 cases and deaths were available, once we adjusted for age differences, Latinos, in fact, were contracting the virus and dying from it at much higher rates than Whites.

The Bigger Picture—The COVID-19 Color Line

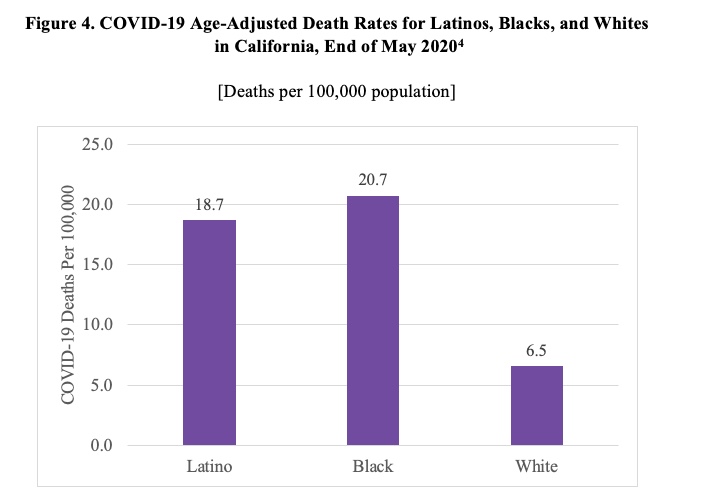

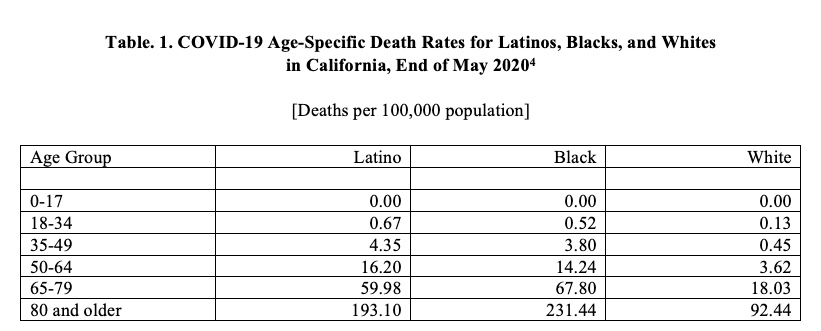

I use data for California, which is one of the few states that provides COVID-19 cases and deaths broken down by age for racial and ethnic groups, to illustrate the value of taking age differences between Latinos and other groups into account. I focus here on age-specific COVID-19 deaths among Latinos, Blacks, and Whites.4 For Latinos in California, the ratio of the percent of COVID-19 deaths who are Latino to the percent of the state’s population that is Latino is 0.97, suggesting that Latinos are slightly underrepresented among California’s fatalities from the virus. I use the California age-specific COVID-19 deaths for the three groups alongside 2018 American Community Survey (ACS) population estimates to compute the age-specific death rates (ASDRs) to allow me to calculate age-adjusted death rates (AADRs) which take into account age composition differences across the three groups.1 The results show that Blacks (20.7 deaths per 100,000 persons) and Latinos (18.7) are approximately three times as likely to die from the COVID-19 virus compared to Whites (6.5) (Figure 4).

Moreover, as evidenced by the age-specific death rates (number of deaths per 100,000 persons in a given age group), Latinos and Blacks are much more likely to die from the virus than Whites across the six age categories (Table 1). Indeed, compared to Whites, at ages 18 to 24, Latinos are five times and Blacks four times more likely to succumb to the COVID-19 virus; at ages 25 to 49, Latinos are about ten and Blacks eight times more likely; at ages 50 to 64, Latinos and Blacks are approximately four times as likely; at ages 65 to 79, Latinos and Blacks are more than three times as likely; and at ages 80 and older, Latinos are Blacks are more than twice as likely to die than Whites. Thus, it is clear that people of color are much more likely than whites to catch the virus and die from it.

Conclusions

A month ago, I prepared a research brief that showed early information on COVID-19 cases and deaths among Latinos.1 Over the last month, things have gotten worse for Latinos. Today, Latinos are overrepresented among COVID-19 cases in 43 of the 44 states that report cases for Latinos. In addition, the number of states where Latinos are evenly or overrepresented among COVID-19 fatalities has risen from one a month ago to seven today, even though it is clear that once age-specific COVID-19 deaths become available, it will be apparent that Latinos are likely to die at much higher rates than Whites.

As the analysis presented here shows, the COVID-19 virus has disproportionately hit Latinos and Blacks while sparing Whites, despite large portions of Whites concentrated in ages where the odds of succumbing to the virus are relatively elevated. University of California, Irvine sociologist, Sabrina Strings, reminds us that preexisting chronic health conditions are conveniently blamed for the disproportionate COVID-19 infections and the deceased among African Americans and other people of color, this is an easy and convenient red herring that cloaks the deep historical structural racism that is as the root of such health issues.5 Strings eloquently asserts that White perceptions regarding Black lives extends back to slavery where Whites came to see African Americans as requiring only the “bare necessities” to exist, “not enough to keep them optimally safe and healthy.” Strings argues that this white reasoning has brought about African American’s lack of access to “safe working conditions, medical treatment and a host of other social inequalities that negatively impact health.” The outcomes of which we see today in the high rate at which Blacks are contracting and dying from the COVID-19 virus.

In a similar fashion, we can see the ways that historically since the mid-19th century in the Southwest, Whites have seen Latinos as needing only the “bare necessities” to exist. We have a long history of receiving the bare minimum including more recently a tremendously unequal funding system to support public education, in which a Texas judge acknowledged that the state’s school funding system was “byzantine,” but adequate,6 and in the CARES Act undocumented workers, who pay taxes and are disproportionately on the frontlines and in essential industries, were excluded from receiving a stimulus check, as were their U.S.-citizen spouses.7

The bare necessities narrative applies to Native Americans as well. The Navajo Nation now has a higher number of COVID-19 infection cases per capita than all of the states in the country.8 On reservations, many Native Americans do not have running water to be able to use soap to kill the virus. In addition, the U.S. government provides a mere 45 cents for each Native American individual for health care through the Indian Health Service for every $1 that the Bureau of Prisons allots to cover the health care of the nation’s prisoners.9 In New Mexico, while Native American make up 9% of the state’s population, they account for 60% of the COVID-19 cases.2

In sum, the massive demonstrations protesting the evil murder of George Floyd sets the context in which the United States has placed lesser value on the lives of African Americans, in particular, and people of color more broadly. The data trends presented here suggest that people of color have borne the brunt of the COVID-19 virus and the pandemic is nowhere over yet. Things will only get worse in the near foreseeable future, intensified by states increasingly opening up for business and by the massive demonstrations resulting from a White policeman savagely taking the life of George Floyd.

Rogelio Sáenz is professor in the Department of Demography at the University of Texas at San Antonio. He is co-author of the book “Latinos in the United States: Diversity and Change.” Sáenz is a regular contributor of op-ed essays to newspapers and media outlets throughout the country.

Endnotes

1 Rogelio Sáenz, “What do we know about COVID-19 infections and deaths among Latinos?,” Latino Decisions Blog (May 4, 2020), https://nalcab.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Article-6_Latino-Job-Loss-in-the-Last-Months-of-the-Covid-19-Pandemic_v3.pdf.

2 The COVID Tracking Project, “Racial Data Dashboard” (May 30, 2020), https://covidtracking.com/race/dashboard.

3 Leah Douglas, “Mapping Covid-19 outbreaks in the food system,” Food & Environment Reporting Network (April 22, 2020), https://thefern.org/2020/04/mapping-covid-19-in-meat-and-food-processing-plants/; Leah Douglas and Tim Marema, “Rural counties with Covid-19 cases from meatpacking have infection rates 5 times higher,” The Daily Yonder (May 28, 2020), https://www.dailyyonder.com/rural-counties-with-covid-19-cases-from-meatpacking-have-infection-rates-5-times-higher/2020/05/28/; Jonathan W. Dyal et al., “COVID-19 among workers in meat and poultry processing facilities—19 states, April 2020,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69 (18), 557-561, May 8, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6918e3.htm#T1_down.

4 California Department of Public Health, “COVID-19 race and ethnicity data” (May 31, 2020), https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/Pages/COVID-19/Race-Ethnicity.aspx.

5 Sabrina Strings, “It’s not obesity. It’s slavery,” New York Times (May 25, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/25/opinion/coronavirus-race-obesity.html.

6 Kiah Collier, “Texas Supreme Court rules school funding system is constitutional,” The Texas Tribune (May 13, 2016), https://www.texastribune.org/2016/05/13/texas-supreme-court-issues-school-finance-ruling/.

7 Jennie Jarvie, “These U.S. citizens won’t get coronavirus stimulus checks—because their spouses are immigrants,” Los Angeles Times (April 20, 2020), https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2020-04-20/u-s-citizens-coronavirus-stimulus-checks-spouses-immigrants.

8 Trace William Cowen, “Navajo Nation now reporting more COVID-19 cases per capita than any U.S. state,” Complex (May 11, 2020), https://www.complex.com/life/2020/05/navajo-nation-reporting-more-covid-19-cases-per-capita-than-any-us-state.

9 Nicholas Kristof, “The top U.S. Coronavirus hot spots are all Indian lands,” New York Times (May 30, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/30/opinion/sunday/coronavirus-native-americans.html?smid=fb-share&fbclid=IwAR2BdCjTY5P_OUO3JJiryQOQrWaTxX-MZUCR1e9dYjt3BSBpUq8q2DuxvW4.