Originally published in The New York Times Opinion section 12/18/2018

Despite major defeats in 2018, President Trump and his Republican supporters are still screaming about so-called border security, demonizing migrants, unleashing tear gas on asylum-seekers and demanding billions in taxpayer money for a wall. It’s as though Mr. Trump continues to see himself descending that escalator in 2015 to bash Mexican immigrants. In 2018, this was a recipe for losing the House. The new showdown over the $5 billion border wall is likely to further alienate Mr. Trump from a majority of Americans.

In the 2018 midterm elections, as the world saw, Mr. Trump and the Republican Party charted out a campaign strategy that focused heavily on stoking fears about immigrants. Their closing argument couldn’t have been clearer. Republicans were blaring racist statements and ominous images of immigrants, calling them murderers, rapists and invaders. They hoped these ads, run by Republican candidates up and down the ticket, would resonate with white Americans who would save their House majority.

But it didn’t work. Enough whites did not feel motivated by Mr. Trump’s immigrant bashing to vote for Republicans. On the other hand, millions of Latinos, African-Americans and Asian-Americans were motivated by it to vote for Democrats.

This was the second major defeat during the Trump presidency for a campaign strategy centered on racism and attacking immigrants, even after it helped propel Mr. Trump to victory in 2016. In the 2017 election for governor of Virginia, the Republican candidate, Ed Gillespie, tried this exact plan and it resulted in backlash from Latino and black voters, and no net gain in turnout or Republican votes from whites.

According to the 2018 American Election Eve poll of voters in the 70 most competitive House districts, which my organization, Latino Decisions, helped conduct, this is precisely what happened in the midterms too. The Republican Party’s anti-immigrant campaign failed to produce a white boost for its candidates.

Most political science research, including my own, concludes that in 2016, Mr. Trump did mobilize white voters who felt left behind and angry at immigrants, blacks and Muslims. But in 2018, voters had had enough: in the Election Eve poll, 57 percent of white voters in swing districts said Mr. Trump’s words and deeds made them angry. The net gain that Republicans thought they could count on from whites disappeared, with 50 percent now agreeing that Mr. Trump and the Republicans were using toxic rhetoric to divide Americans.

Likewise, no real evidence emerged in 2018 of a white base mobilized by attacks on immigrants. This is not to say that some white voters do not enthusiastically support Mr. Trump’s anti-immigrant agenda; they do (49 percent said immigrants were a threat to America). But after two years of Mr. Trump’s anti-immigrant policies, their numbers are getting smaller. Nationally, there was no evidence of a surge in white Republican votes for anti-immigrant candidates.

As Mr. Trump continues his anti-immigrant agenda in his fight with the likely new House speaker, Nancy Pelosi, it is important not to lose sight of just how thorough the defeat of anti-immigrant candidates was in the midterms. Sure, some anti-immigrant candidates won, but those were mainly in very heavily Republican districts, and even some supposedly safe Republicans lost. Prominent Republicans who championed Mr. Trump’s immigrant-bashing lost their election bids, from Kris Kobach in Kansas to Lou Barletta in Pennsylvania, and from Corey Stewart in Virginia to Dana Rohrabacher in California.

The national immigration advocacy group America’s Voice has compiled a list of 31 House Republican candidates in 2018 who echoed Mr. Trump and lost their elections. In Arizona, Republicans had high hopes for Martha McSally to hold Jeff Flake’s Senate seat, but she ended up supporting Mr. Trump’s full immigration agenda, and she lost, in part, because of Mr. Trump’s anti-immigrant message. Although Ron DeSantis, an anti-immigrant Republican, won the governor’s race in Florida, he was one of the only successes among a string of defeats. In Nevada, the incumbent Republican Dean Heller invited the president to stump for him. Mr. Trump railed against immigrant gang members. Senator Heller lost to a proponent of immigration reform, Jacky Rosen.

So did Republican attacks on immigrants mobilize any voters in 2018? Yes, but it came in the form of Latino voters who reversed their record-low turnout in 2014 with record-high turnout in 2018. In the Election Eve poll, 73 percent of Latinos said Mr. Trump made them angry, while 72 percent said that they felt disrespected. Forty-eight percent of Latino voters agreed that Mr. Trump is a racist whose policies are intended to hurt Latinos, and27 percent said that Trump policies have had a negative impact on Latinos, while 18 percent said Mr. Trump was having a positive impact on Latinos.

In 2001, the political scientists Adrian Pantoja, Ricardo Ramirez and Gary Segura established that perceived immigrant attacks have a strong mobilizing effect among Latino voters. In 2018, Latino voters once again proved that thesis correct.

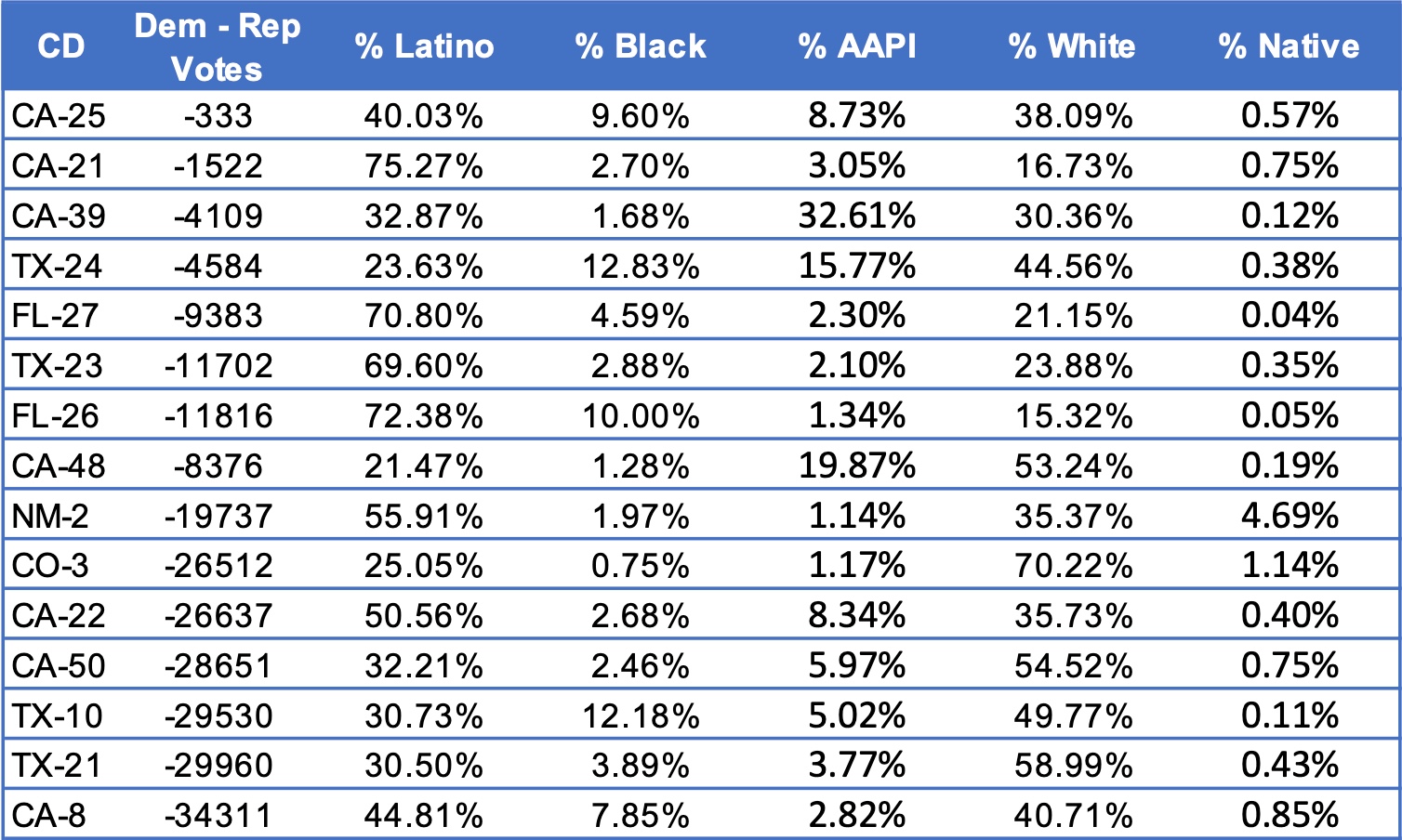

In California, Latino voters increased their turnout enough to oust five Republican incumbents and help Democrats pick up two open seats. In Texas, Democrats won two House seats where Latino turnout was up. In New Jersey, Democrats gained four seats. Next door in New York, Democrats picked up three seats. There were two more Democratic pickups in Latino-majority districts in Florida, and one each in New Mexico and Arizona, while Democrats held on to two hotly contested seats in Nevada.

A recent analysis by the Latino Policy and Politics Initiative, a research center at U.C.L.A. that I helped found, revealed that across eight states with sizable Latino communities, the Latino vote grew by 96 percent from 2014 to 2018, compared with a more modest 37 percent in growth in the votes cast by non-Latinos. In a postelection analysis, Latino Victory Project and the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee noted that early voting among Latinos increased by 174 percent. The U.C.L.A. study also concluded that higher Latino turnout was influential in flipping 20 of the 40 House seats that Democrats gained.

When asked how they engaged were by the 2018 election, 77 percent of Latino voters in the 70 swing districts identified by The Cook Political Report said that they actively encouraged their friends and family to vote. But it was not just self-mobilization; campaign outreach mobilized Latinos. In these 70 competitive districts, 53 percent of Latinos said someone contacted them and asked them to register or vote, thanks in part to efforts by the D.C.C.C., which invested $30 million in targeting Latino voters in battleground districts (My firm, Latino Decisions, worked with the D.C.C.C., although I did not work on any direct efforts for candidates.)

So what does this mean for 2020? First, it’s going to be much harder for Mr. Trump and Republicans to persuade Americans that immigrants are ruining our country. Before Mr. Trump took office, Republicans were more trusted than Democrats on immigration, but now it’s Democrats who are more trusted.

Nonetheless, Mr. Trump will continue attacking immigrants in 2019 and 2020. Indeed, he vows to shut down the federal government to get his border wall. While he is likely to get standing ovations at his rallies when he denigrates immigrants, the number of voters who favor the his immigration agenda is shrinking. Perhaps worse news for the Republican Party is that many Latino voters view Mr. Trump’s deeds, words — and the man himself — as racist, and the 2018 election demonstrated that the community is eagerly awaiting its chance to vote him out in 2020.

Matt A. Barreto (@realMABarreto) is a professor of Chicano studies and political science at the University of California, Los Angeles, a co-founder of the polling firm Latino Decisions and the author of “Latino America: How America’s Most Dynamic Population Is Poised to Transform the Politics of the Nation.”

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.